Defunct sanatorium and prison still has more to teach

The complex was slated to become a hydroponic farm, but people kept ‘trespassing to see the place’

Pennsylvania’s Cambria County is full of wooded hills, clear water creeks and historic hamlets. Brochure stuff. However, one of the most important locations in the rural county does not fall in line with the postcard settings that surround it. It’s for that very reason that it’s so significant.

The Cresson Sanatorium and Prison opened as (you guessed it) a sanatorium in 1916, and was eventually repurposed as a (right again) prison in 1986. Throughout its history, the grounds served as a tuberculosis sanatorium, psych center, state school, and then underwent heavy modification to become SCI Cresson, a medium-security prison. When the prison closed in 2013 it sat in a state of abandonment for years.

I was invited down to the property by my longtime friend Ray Staten, a tour guide at the grounds. Big House Produce, a hydroponic growing operation, bought the vacant property in 2019 with the intention of repurposing the empty cell blocks to grow lettuce.

“When we got the property, people kept calling, asking to see the place,” said Staten, an employee of Big House Produce – “trespassing to see the place.” Initially the idea was to let some people in, he explained, allow them to see the structures, and then go about converting the blocks into the intended farm. However, the amount of interest, and the reactions that the buildings were stirring in those who visited, prompted a change of course. “As we talked to the people and learned the history, and a lot of the social issues and criminal justice issues, we were like, there’s a lot more important things we can be doing with this property,” said Staten.

The company decided to convert only the juvenile building to a farm and open the rest of the grounds to public tours, guided or self-guided. Visitors who opt for the latter option can wander the grounds and buildings at their leisure, with friends or alone, to experience the 34-acre property with its century of history. On my day there, the group tour included a mother and teenage daughter, an elderly couple and a group of about a dozen costumed young adults doing a series of photoshoots. Of the wide spectrum of people who come through – including ghost hunters and history buffs – a few have stuck with Staten in particular.

“There’s a lot of groups of people this place can help, but one we didn’t expect were the former inmates. They come back as a form of closure,” he said. “The experience of being in prison leaves them with basically PTSD and trauma that’s hard for them to deal with.”

One former inmate came alone to see Cresson, opting to do a self-guided tour and wander. “He was absolutely terrified to come here,” said Staten. “We took him into building J so he didn’t have to do it alone.” Building J is a massive “restrictive housing” unit, much like solitary confinement.

“As soon as he got in that cell block he broke down in tears, telling us all about his experience. It was one of the most moving experiences of my life.” That tour ended with an exchanging of hugs and gratitude from the former inmate, who told staff that his visit was helping him get past his traumas. Currently Cresson is working on reaching out to support groups so that in the future former inmates may come as a group, to be there for each other throughout the experience.

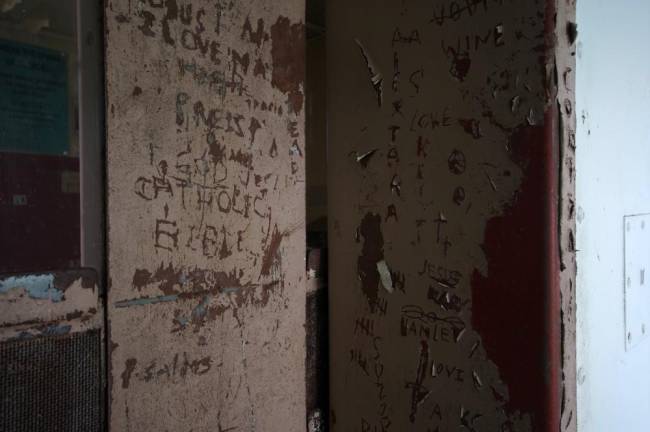

The second story deals with one of the more heinous bits of Cresson’s history. Back when the prison opened, it featured a small pair of security blocks for housing inmates in solitary confinement called the Restrictive Housing Unit. With its solid steel doors, human cages, and tiny courtyard where four people at a time could stand in cages for sunlight, the RHU was constructed for inmates serving intense sentences, who typically were locked in their cell 23 hours a day. When the prison population outgrew that space, a huge, new structure went up. The old cell blocks – the worst on the property – were then used to house mentally ill inmates, with no alternations made to the cells.

Today, visitors can walk the ward and sit in the very same cells. “It’s easy to just tell someone they took a mentally ill person and locked them in this building. It’s easy for a person to brush that off,” said Staten. “Have that same person on a tour, have them stand in that cell and tell them that they locked a schizophrenic person in here for 23 hours a day, it hits very differently.”

A certain genre of visitor comes in with a “don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time” mindset. They tend to be easy to pick out from their jokes and offhand comments about being locked up, said Staten. “People who didn’t believe in prison reform, that solitary confinement was OK,” Staten said. “Then you get to that RHU building and they stand in a cell.” It’s not uncommon for those visitors to switch gears, talking openly about how awful life must have been for those in the RHU. “You can tell that their views are starting to change.”

What’s striking about the Cresson property is that there are structures standing from every era of operation, from sanatorium to prison. Though some are quite old, the lessons they hold are as poignant as when they were built and in some cases moreso, offering a strong catalyst in opening dialog not only on prison reform and mental health, but also physical health and child development. Building 1 stands at the far end of the grounds, a holdover from the sanatorium days. It housed the children of families exposed to tuberculosis, in an effort to prevent their infection. Buildings like these were called preventoriums, and Cresson may hold the last surviving one in the country. It’s an upsetting look back in time, and that’s what makes places like Cresson so vital to our collective future. But the future of Cresson itself is in jeopardy.

The operators of the Cresson Sanatorium and Prison leased the property with intent to buy, however their plans with the landlord have hit turbulence and their lease will not be renewed at the end of its term. If Big House Produce doesn’t raise the money to buy the property by 2025, it will be sold to a different developer, who may not have any intention of retaining the structures.

“I think about the people and inmates we’ve helped,” said Staten, “and I don’t want that to disappear for everyone.”