A heavy toll

Our obesity epidemic made us a soft target for Covid. Could this be a tipping point?

Martha Echevarria, of Greenwood Lake, NY, had always been on the chubby side. “But in the last 10 years, I guess when I start having menopause,” she said, “my weight gained significantly.”

She’d tried different diets and exercise regimens, but she’d always gone back to old habits and the weight returned. At five feet, pushing 260 pounds, it got to the point where it was hard for her to pick things up off the floor or cross the street, let alone keep up with her 10-year-old grandson. (Echevarria prefers “chubby” to “obese.” We’ll use obese when we mean specifically a body mass index of 30 or more; severe obesity is a BMI of 40 and up.)

“I was really feeling pretty down,” said Echevarria, 64, a social worker at Rockland Psychiatric Hospital’s outpatient mental health clinic in Middletown. “Now I realize that it was so hard to do anything physical because I was getting tired, no energy at all. I could feel that it really affected me drastically. I was not really doing well.”

After a doctor visit last September, Echavarria got an ultimatum. “If you continue with this you are not going to be with us for too long, because this is too much,” she recalled. Her alarming bloodwork, she learned at a follow-up with a specialist, was a result of fat pressing on her kidneys.

“I got really scared,” she said. So did her family. Already, severe obesity threatened to end her life early, and now Covid-19 could turn “early” into “right now.” The virus was preying disproportionately not only on the elderly and people of color, but also the obese, a category that now includes more than two in five Americans. “I was really scared of ending up in the hospital and having problem with my breathing. So that also made me realize I really have to do something,” she said.

Being overweight worsens Covid outcomes across the board, coming in a close second behind old age as the biggest risk factor, according to a new report from the World Obesity Federation. The bombshell study revealed that the risk of death from Covid is profoundly greater – about ten times higher – in countries where most of the population is overweight, according to mortality data from 160 countries. Mortality rates increased hand in hand with a country’s prevalence of obesity. That helps explain why the United States, one of the fattest countries on earth, accounts for over a fifth of Covid’s global death toll.

Before Covid came along, revealing hidden fault lines, chronic disease was paving the way for the virus. The modern American plagues of obesity, diabetes, stroke, heart disease and cancer all hit harder in communities of color, leaving these under-insured, lower-wage communities extra-susceptible to the ravages of Covid.

When it comes to obesity, rural areas are particularly heavy, as are people without college degrees. Black adults suffer from the highest rates of obesity nationwide, at 49.6 percent, while Hispanics like Echevarria, who is from Peru, rank second at 44.8 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That’s the bad news. But there may be a silver lining, if we can do what no country has ever done before: harness the disruptive energy of this moment to turn this battleship around.

This time, it’s life or death

Echevarria found herself sleeping a lot during the lockdown, like the rest of the world. But once the Middletown Y re-opened its doors in November, she got in gear. She started working out twice a week there, impressed by how clean they kept it. Her daughter also got her sessions with a personal trainer for Christmas.

She renewed her focus on her diet, eating more fruits and veggies and lean protein like fish, and cutting back to a serving a day of carbs. Born in Peru, rice had always been a staple of Echevarria’s diet, but now instead she might have whole wheat bread or pasta, oatmeal, quinoa. “And for snacks I have good snacks,” she said. “Granola bars but good ones.” Sweets are a hard no. When she made an exception and ate dessert over the holidays, the next day she felt sick.

Echevarria had dropped 22 pounds when we spoke in January. “I can feel I can do a lot more physical things than before. I have more energy,” she said. “I don’t get tired as much, I’m able to go up and down stairs. Little thing that you may say, well that’s nothing, for me it’s a lot.”

Junk food, junk food everywhere

Did Echevarria ever feel othered because of her weight? “Not really,” she said – not in America, at least, where she has lived for 36 years. She goes back to Peru almost every year, “and every time I go, they say, ‘Oh my God, what happened to you?’ I say, ‘I know.’”

“Let me tell you, over there, society puts so much weight that you need to be skinny and you need to be looking nice and stuff like that, that you really force yourself to be skinny,” said Echevarria, of her birth country. “‘Cause even when you go to the store, you are not able to find plus sizes there. Here, it’s incredible, because heavy people can go to the store and get plus sizes and nobody says anything. Over here, it was comfortable to get bigger. Clothes is not a problem, food is in abundance. But where I come from, you could not be fat in middle class people.”

America today is not only a comfortable place to get bigger, it’s a devilishly hard place to avoid it. Echevarria’s weight does not put her in a marginal group of Americans, far from it. With more than 73 percent of Americans carrying extra pounds, according to the CDC, being a healthy weight or having healthy blood pressure actually now puts you in a fast-shrinking minority in our country. “Even at my job, there are women who are double my size,” said Echevarria. “You think I’m heavy, imagine how heavy they are.”

With a foot in two countries, Echevarria has some insights about how America got supersized in such a hurry. “I think it’s because food is available everywhere, right?” She points to the unrelenting availability of junk food, epitomized by the candy bowl at her work. “And really, eating healthy is very expensive, while you eat junk food and it’s cheap,” she said. “You can get a bag of potato chips and just pay $2, you know. So it’s easy to gain so much weight because bad food is cheap.” In Peru, where food is less abundant, portions are by necessity a lot smaller, she said.

Weight gain is a complex issue that goes way beyond food, with roots woven through our flawed social and pharmaceutical-industrial systems. We’re stressed, isolated and sedentary. Many avoid the doctor in America, the last of the world’s 25 richest countries without universal health care.

It’s complicated indeed, but Echevarria’s instincts drive to the heart of the problem: the highly processed American diet is the biggest culprit when it comes to making us fat and unwell. We’re swimming upstream against a trillion-dollar food megalith devoted to aggressively marketing us empty, hyperpalatable calories at a fraction of the price of real food. Poor diet leapfrogged smoking five years ago as the leading cause of early death in this country. Big Food is killing five times more Americans than gun violence and car accidents combined.

The elephant in the room

Weight is such a loaded topic – steeped in misogyny, fat-shaming, systemic racism, mental health issues, food apartheid – that it’s not hard to see how it has become the elephant in the room. Over the dinner table, on Zoom calls with grandparents, in the media, even in medical school and the doctor’s office, we’d rather talk about anything else. Put it up there with religion and politics and wave off any allusions to the midsection: the camera adds 10 pounds.

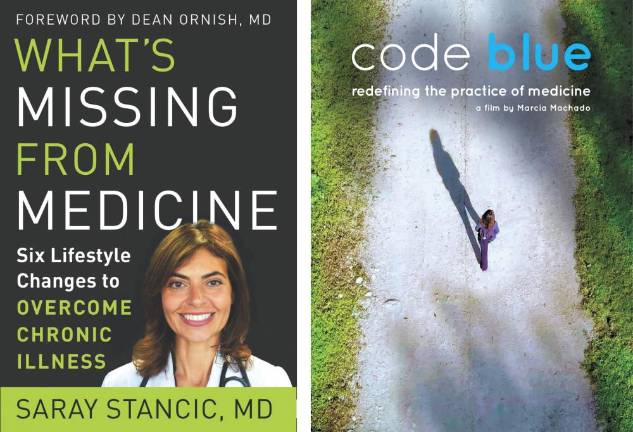

“As I watched this tragedy unfold, it became clearer than ever that most people don’t want to have the difficult conversations with their friends, family members, and even themselves that this crisis is demanding of us,” wrote Dr. Saray Stancic, author of What’s Missing from Medicine: Six Lifestyle Changes to Overcome Chronic Illness (2021), in her Covid-inspired preface. “This is also true for many of my fellow doctors, who often avoid having the harder conversations with their patients about their lifestyle choices.”

Depending on how it’s delivered, after all, hearing what you may know all too well – that you should eat better and exercise more – can come off as patronizing, judgmental, even traumatizing. It can also backfire, making heavy people hesitant to see a doctor for any reason, for fear even a routine gynecology appointment might turn into yet another finger wagging. Fat stigma can exacerbate weight problems, making heavy people avoid the gym, triggering a stress response to eat. Studies suggest stigma may be even more deadly than excess weight itself. The week in March after the World Obesity Federation report dropped, identifying obesity as a major Covid risk factor, watchdogs reported a rise in weight-shaming comments on social media.

“I think we have to be very sensitive as to how we approach the topic, particularly for women,” said Stancic, of Bergen County, NJ. “My approach to any patient, I say, ‘I’m going to speak to you honestly. First I’m going to develop a relationship of trust, and I’m going to share the good and the bad and I’m going to be honest,’ and we have to do that in a very respectful and sensitive fashion, for sure.”

Stancic has no problem being something of a Cassandra. A slight, first-generation Cuban-American, she is known for pulling on her sneakers and going walking and grocery shopping with her patients. She is also known for pulling no punches. It’s time to quit blaming our genes, she says, and wake up to fact that we have the power to reverse 80 percent of chronic disease with a few relatively simple changes. They boil down to: eat well, stress less, move more, love more.

Her patients are often shocked when she tells them they’re obese, but she doesn’t let that stop her. “I would rather tell someone the truth in the short term and help them stay alive and healthy than keep quiet and lose them to preventable death by staying ‘polite,’” she wrote. “Most doctors would rather write a prescription for prediabetes than counsel and support a real weight loss strategy, and this is part of a disturbing lack of perspective in medical education and practice. From solo physicians up to our largest hospitals, glaring omissions in education and treatment are literally killing us.”

Stancic has made it her life’s work to right our broken healthcare system, speaking out for common sense changes from the individual scale (move every day, spend quality time with loved ones) to societal (teach medical students how to promote health rather than just treat disease). In addition to her book, in the past couple years she produced a movie, Code Blue: What Your Doctor Doesn’t Know Will Shock You (2020), and led doctors in a protest to get the Burger King out of University Hospital in Newark.

That we are still feeding hospital patients the very diet that made them sick is a telling example of how far society has to go. Stancic recalled how smoking in hospitals was standard fare when she was a medical student in the 80s – unthinkable now.

When it comes to being the bearer of tough news, it may help that Stancic has been through the ringer herself. Like 60 percent of Americans today, she faces her own lifelong battle with chronic disease, having groped her way back to health from the ravages of multiple sclerosis. She walked the walk, quite literally, jettisoning her prescriptions, walker and even diapers decades ago and finding her therapy in a plant-based diet and endless miles in those signature sneakers. These days, she bangs out three to five miles every morning after breakfast.

As the former chief of infectious diseases at the Hudson Valley Veterans Administration Hospital, Covid happens to fall squarely at the intersection of Stancic’s areas of expertise: pandemic preparedness and chronic disease. In those two basic areas, America – sophisticated as we are at acute care and complex therapies – is floundering.

“A virus like this, unleashed in an environment where chronic diseases are commonplace, can wreak irreparable destruction,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

“Our country is so messed up about weight”

“I always struggle to speak with people about weight, because I think our country is so messed up about weight,” confessed Madeleine Ziegler, a nurse practitioner in Goshen. “I have tried to be so gentle with my patients who have gained weight because they are obviously struggling on multiple levels. There is already so much weight stigma, which makes people less healthy. I try to focus on really small positive changes they can make to better care for themselves and better address the stress.”

Ziegler urges patients to start moving their bodies in any way that doesn’t feel like “a total drudge”: walking, dancing, playing a sport. Ditch the no pain, no gain mentality. The important thing is finding something that you can incorporate into your life for the long haul. And be patient with yourself. “True, long-term change is difficult, and gradual, and requires a full lifestyle change, not just a restrictive, prescribed diet.”

Weight has always been a fine line for medical professionals to walk, and that’s never been more true than in this year of seesawing scales and fragile psyches. “Some people will come pre-loaded with, if he says anything about weight I’m going to fold, I’m going to cry or I’m going to kill him or never come back,” said Dr. Alan Schaffer, of Goshen, a pulmonologist and critical care doctor who specializes in the closely linked fields of sleep medicine and obesity. “There are people who’ve been traumatized by their physicians.” Even when doctors know better, many have a hard time masking their dismissive, judgmental reactions to patients who struggle with weight, he said.

Schaffer says he wouldn’t take weight loss advice from anyone who hadn’t been through it themselves. But even though he is a part of that club, approaching weight can still feel like walking on eggshells. He tends to back into weight loss by first helping patients with their sleep apnea. Once they’ve had their first good night’s sleep in years and are feeling good and primed, he’ll mention, “Hey, I do weight loss too,” and they usually say, “Let’s do it.”’

At 61, with the sense of urgency mounting, Schaffer has gotten bolder – both in the exam room and out. This year saw him marching in Black Lives Matter protests; critiquing our antiquated healthcare system that profits from chronic disease; calling out the rampant fat-shaming, rooted in a racist caste system, that he sees in and out of the medical community; and on a lighter note, playing the Mozart clarinet concerto with the Greater Newburgh Symphony Orchestra.

Over the years, he has matured into a bedside manner that allows him to be direct without putting off his patients. “I’ve noticed that when I approach patients without judgment, but with general concern for their wellbeing, I am more likely to be met openly,” he said. He recalls one particular patient who had seemed resistant to everything, then surprised Schaffer by his openness to, and eventual success with, a weight loss program. Now, said Schaffer, “unless I’m clearly met with anger or resentment and don’t have a good rapport with the patient, I will always bring it up.”

“I could have saved that one”

Covid has changed us all, but few as powerfully as doctors like Schaffer, who spent last spring watching patient after patient die hooked up to a ventilator in the St. Anthony’s intensive care unit in Warwick. “I’ll tell you, the stuff I’ve seen, and I was only at little old St. Anthony’s... I would run the codes when they went into cardiac arrest.” So many of the people dying were heavy. “Even when I watch TV and they say this is someone who died, I see pictures, I mean they’re all overweight. And I just sort of shake my head,” he said.

“I feel like Schindler’s list, when he says, ‘Oh, I could have saved this one, I could have saved that one,’” said Schaffer. “I’m not a big ego guy but when you see what happens when people are overweight and obese, the bottom line it’s the effect on the immune system.”

That obesity was a major Covid risk factor came as no surprise to Schaffer. “Well, duh,” he said. “Of course it is, and of course diabetes is,” he said. “When there’s obesity – with all these hormones and high insulin levels, etcetera – you just don’t have the ability to do what your body needs to do, and part of that is fighting off infection.”

Schaffer is particularly haunted by one patient, a bright, functional, obese 50-year-old who was hospitalized for Covid along with his father. It was Schaffer who was called in at 2 a.m. to put the younger man on a ventilator, and later, who had to call the man’s mother to tell her that her son had died; days later, her husband would die, too. It was the hardest thing Schaffer had ever done.

That 50-year old could well have been Schaffer, if instead of losing 45 pounds over two months in 2008, his own life had taken a different course. “There but for the grace of God go I,” he said. “If I were his weight and maybe with his genes and his disorders it could have been me.”

By the time Covid patients were landing in the ICU last spring, there was little doctors could do for them other than hand-holding. That didn’t mean their deaths were inevitable, though, only that help had come too late.

Root cause medicine

Even as we have come face to face with the dire cost of carrying extra weight, many of us have packed on pounds during the pandemic. “Most of my weight patients I’ve been following over time gained often significant weight over Covid, because of you know, the sadness, depression, the lack of exercise, the fear and the boredom, so people eat. And people who are overweight often have these triggers to make them eat,” said Schaffer.

The pandemic’s fear factor may also provide an opening, however, making us particularly receptive to the idea of making changes we might brush off under normal circumstances. “When I would have a patient for sleep apnea, and I would talk to them about their weight and I would tell them, you know obesity and diabetes are the number one and two risk factors for Covid, they would hear it loud and clear,” said Schaffer. “And, yes, they would be more gungho.”

The harrowing experience of last spring reaffirmed Schaffer’s commitment to what he calls “root cause medicine.” The end game of root cause medicine – after treating symptoms like high blood pressure and sleep apnea – is to get patients off all their medications and sleep gadgets, feeling well and functioning better at work. It’s a win-win in terms of quality of life and cost to society. The only problem is, a doctor can’t actually make a living that way. Primary care physicians get 15 minutes for each appointment, enough time to write a prescription for a CPAP machine for sleep apnea, but not enough to go deep into what they’re eating.

“It doesn’t pay,” said Schaffer. “If I see a patient for weight management it’s not going to pay,” said Schaffer. “That’s why I’m hoping that one of the things that comes out of Covid, a silver lining, is that obesity is taken seriously. It’s starting to.”

In the meantime, Schaffer would have to jerry-rig a solution. He decided to partner with a nutrition coach who could provide patients the sustained attention people need to really lose weight.

Enter Amy Bandolik, a career coach and food tour guide from Cornwall, NY, with whom Schaffer connected last fall via Facebook over politics. The conversation turned to weight loss, since Bandolik was looking to shed 15 pounds, and Schaffer gave her the scoop on the keto diet that he swears by. (Here’s a good place to mention that Dirt doesn’t endorse any particular way of eating other than local. You’ll notice that the high-fat, protein-heavy keto diet and Stancic’s recommended plant-based diet are at odds. What they have in common is avoiding highly processed “foodstuffs,” as Stancic calls them, like sugary cereals, chips, prepackaged pastries and cookies.)

Bandolik sat on the idea – a strange one for a lifelong low-fat dieter – for six months, until the pandemic hit and shut down her office and suspended food tours. “I have time and space,” she said to herself. “I will do an experiment.”

She started eating totally differently than she’d ever eaten – eggs cooked in butter or drizzled in olive oil, with bacon and avocado on the side. She spent a lot of time browsing farmers markets, “cooking for myself and eating real, actual food,” as opposed to her old commuter’s routine of grabbing a packaged lunch from Starbucks and occasionally indulging her sweet tooth by downing a pint of Ben & Jerry’s.

Bandolik shed 22 pounds, blowing past her goal to pre-baby weight. “It was about feeling good, feeling lighter, and wearing a bikini,” she said, “which contributed to self-esteem and happiness.” She was sold. She got certified as a ketogenic nutrition coach over the winter, posting client success stories on social media between photos of sizzling sausages and chicken wings hot out of the air fryer. Schaffer can now refer his weight loss patients to Bandolik. He has finally found a way to do root cause medicine, and judging from the new “KETO DOC” vanity plate on his Subaru, he’s done keeping quiet about it.

The shake-up

The pandemic has been the biggest rule-breaker we’ve seen in a century. An army of workers found themselves untethered from their desks and cars, and for many, the nine-to-five office job that has defined us for generations may now be a thing of the past. While more than 40 percent of us put on the “quarantine 15” or worse this year, there is a counter-trend of people like Bandolik, who’ve taken the time they once spent commuting and flipped it.

“Everybody’s Facebook feed was like, I’m gardening, I’m cooking,” said Bandolik. “And you saw people feeding themselves in a way previous generations – our grandparents – fed themselves. You’re controlling ingredients, you’re not eating out. The idea that we can take time out of our schedule and not just fill it in with work but cook for ourselves is something that I saw across the spread of the pandemic. There has been some freedom of reinvention and a little bit of power back to the people.”

John Donahue of Warwick, NY, could be the poster boy for this counter-trend. The owner of an advertising firm, he went into the pandemic with weight to lose. After being put on beta-blockers the summer before, his weight had ballooned from 200 pounds to 260. At 44, he could no longer skydive because landing was too risky at his weight. When the world shut down, he was three months into being cleared for physical activity and had already started to shed weight. Now, his focus crystallized. “I made the commitment to myself: It’s Covid-19, so let’s make it Covid minus 19.”

Now that he wasn’t commuting to the city three days a week, he could devote two hours a day to “run, boy, run,” as he put it. When gyms reopened, he started going to CrossFit seven days a week. By the time we spoke last fall, he had shed his “Covid 19” and then some, and was running 5Ks with his eight-year-old daughter.

Will healthy habits carry through into post-pandemic life? That’s the sixty-four thousand dollar question.

“I’ve seen that when people are impacted by something so profound as this, it’s often a catalyst for change,” said Schaffer, in a video that his nephew helped him make at the height of the first wave. Sitting in his house, sometimes with his white coat still on from his shift, Schaffer broke down crying a number of times, as he tried to put words to the devastation he was witnessing at the hospital. “For people to really look at their lives, look within, and ask themselves, Wow, what’s going on here? What am I? Who am I? How have I been living? How could I live my life in a way I prefer?”

There’s no denying the deck is stacked. For families whose breadwinners have lost jobs, decent food is now even further out of reach. Essential workers who’ve been working double-time for over a year now do not have a lot of time for cooking or working out.

But for a swath of Americans like Bandolik, Donahue and Echevarria, this strange year offered a once-in-a-lifetime chance to radically reorder their priorities. “If anything can have a lasting impact,” said Bandolik, “it’s this.”

A uniquely modern friction

“Not sure if you saw the cover of Cosmo UK,” Dr. Stancic wrote me in January. “There is most definitely a move to expand the definition of good health. It’s got me worried.”

The February magazine cover in question is unremarkable these days for featuring big women in workout gear. What sets it apart is the tagline: “This is healthy.” The issue devoted to body positivity set off a firestorm on both sides of the Atlantic. Some applauded the magazine for its radical inclusivity, for challenging a destructive stereotype, for big representation; others lambasted it as irresponsible junk science.

“My concerns revolve around the concept of ‘normalizing’ obesity,” said Stancic, of the Cosmo cover, “and creating a notion that is a healthy alternative. It is not.”

It has never been more clear that shame has no place in the weight equation. One in three kids in school is now fat. Nearly three-quarters of Americans are overweight. Willpower alone can’t shoulder all that blame.

Kindness and understanding are critical, says Stancic, who has treated obese patients who do everything right but still, for reasons we don’t fully understand, do not lose weight. But that does not mean we simply shrug and embrace the new status quo. The paradigm shift that’s required – both on a societal scale and in our daily lives – is not going to come about on its own, she argues, without some hard and compassionate conversations.

As she was fact-checking her book, Stancic discovered that America’s obesity rate had shot up again, to 42.6 percent. “In one year it increased by more than two percent, which is extraordinary. Just when you think it can’t get worse, it gets worse, and we’re not acting to correct it.” At this rate, nearly half of Americans will be obese by 2030, according to projections by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Soft-pedaling the problem – whether on the cover of a magazine or in the doctor’s office – is the opposite of compassion, said Stancic. It is consigning leagues of people to shortened lives that end miserably.

This uniquely modern friction lands on our doorstep electric with tension. The word “fat” itself is caught up in a tug-of-war: still tossed around as an insult, it’s also being reclaimed as an honest descriptor, even a point of pride.

Begin to unwrap your own feelings on the subject of weight and you will find fodder for multiple college curricula. There’s misogyny and the impossible standards that women have been held to since way before Barbie arrived on the scene. There’s the racism-infused diminishment of bodies that don’t fit the narrow standard handed down from on high.

One of the plus-size models featured in the Cosmo UK issue is North Carolina-based yoga teacher Jessamyn Stanley, who makes that last point loud and clear on her provocative blog. A self-described “fat femme,” she posted a picture of herself toking up topless the week after George Floyd was killed. She wore only yoga pants by her fitness company The Underbelly, a community for everyone who feels overlooked and underserved by the wellness industry.

“At this point, the only resistance I know is to live my joy as loudly and freely as I can,” she wrote alongside the topless photo. “I Am My Ancestors Wildest Dream. My joy is my rebellion, my resistance. It is my birth rite and my glory.”

Where to from here?

People all over the globe are getting fatter – at the same time, perversely, as more people than ever are also starving. The decades-long failure “is clearly responsible for hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths,” said Johanna Ralston, CEO of the World Obesity Federation, which works to elevate obesity on the global agenda.

So far, Covid has inspired a few countries to take on Big Food, whose grip has only tightened during the pandemic. In Britain, the heaviest country in Europe, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s hospitalization with the virus inspired him to reverse his libertarian stance on the “nanny state” and push through a $13 million anti-obesity campaign. Announcing, “I was too fat,” he curbed junk food advertising and instituted a task force to incentivize Britons to be healthier. Germany’s head of agriculture also wants to curb junk food advertising, and the Mexican state of Oaxaca passed a law banning sales of junk food and sugary sodas to kids.

Change may be on its way to the United States. The new Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, put it bluntly when he told Politico: “We cannot have the level of obesity. We cannot have the level of diabetes we have. We cannot have the level of chronic disease... It will literally cripple our country.”

But a top-down transformation of our food system is not here yet. “Nothing about our culture has changed as a result of this pandemic,” said Ziegler, the nurse. She lives in Chester, NY, overlooking the black dirt fields where her husband grows organic vegetables – which, in another symptom of a broken food system, he has to drive to Westchester or the city to sell at farmers markets. “We aren’t a culture that moves very much, and healthy food is expensive. Some people have said – I tried to buy more vegetables, and they’re expensive. It’s very expensive to eat well.”

For now, it will have to be an every-man-for-himself battle to reclaim our health, or nearly so. We’re not entirely on own: good or bad behaviors, much like viruses, are infectious, passing to friends and family members, Stancic notes in her book. And on the bright side, we seem to have taken to walking en masse.

“At least in the immediate concern, when I go out in the morning and walk or run, I see more people outside,” said Stancic. “I think there is a sense that this idea of lifestyle and movement is coming in a wave across the country. There’s much more attention to lifestyle and prevention, particularly in medical school. Certainly this millennial generation is much more sensitive to this idea of healthier food options, and it may be tied in to their concern for their environment.”

Echevarria and I met up on a frigid Sunday in March for a walk in the park. Veterans Memorial Park in Warwick was bustling with masked people of all shapes and ages walking their dogs or playing fetch, talking into ear-pieces while power-walking, biking alongside little kids on training wheels.

Echevarria had lost 30 pounds, she reported – an additional eight from two months earlier. She had just joined a resistance band exercise class at the gym, which she liked: it forced her to challenge herself more than she did on her own. In the office, she had been making sure to get up from her desk and walk around regularly. She hadn’t gotten feedback from folks at work – not yet – but her grandson was cheering her on. Her doctor said her numbers looked much better, and she was looking forward to buying herself a new summer wardrobe. She’d been vaccinated for Covid, so that was one health anxiety off her mind.

Avoiding triggers has been key to Echevarria’s success this time around. Steering clear of temptation is not easy in America, where food you don’t want to be eating all but follows you around, often free for the taking, ever-ready to launch you back onto the vicious cycle of weight gain and stress eating.

So she has been avoiding the front common area at her work, where well-meaning colleagues are forever leaving donuts or a bowl of chocolates or candy. “Nobody goes and says let me bring a bowl of fruit salad,” she said drily. “What I notice is that if I don’t try it, if I don’t eat one piece of candy or chocolate or whatever, I’m okay,” she said. “But if I eat one I will eat 10.”

When a doctor recently paid a visit to her office, bringing with him a spread of bagels and cream cheeses, Echevarria managed to walk away. She told herself, “I know what a bagel tastes like.”