The other Greece

A Greek American follows her Yiayia's memories to a refugee camp

When I was a child, Yiayia, my grandmother, would feed us homemade tiropites, spanikopites and countless stories from her happy childhood in Kambia, a farming village in the Greek mountains overlooking Turkey. Of all her stories, I could recite many by heart, especially the one about her family’s journey away from everything they knew in response to World War Two. When my Yiayia was 12, Germans occupied her island, controlling the food supplies and causing many communities to starve and eventually flee or die.

Yiayia would share her story not only at home, but also in line at ShopRite and Costco. As shoppers gathered to listen, she’d highlight the treacherous waters, her sister’s death on the small boat, their long journey to the camp in the Congo (which was then occupied by Belgium), and finally her American visa approval and subsequent arrival in America. She would always end by describing how well the Belgians treated her when she arrived in the Belgian Congo’s camp: “They washed, clothed, fed and taught us,” she’d say. “What do we do now for people in need? We have everything, but do not give. We have everything but are poor in love.”

Fast forward a few years, and as I relax on a beach in Kalamata, Greece during the summer of 2017, our group of 20 Greek-Americans participating in a Greek heritage summer school hears the news of a few dozen refugees arriving on two boats a couple of miles away. We talk about the situation and resume relaxing on the beach, enjoying our free month-long trip to our ancestors’ homeland.

We, a group of able-bodied teenagers, were given the opportunity to lazily enjoy the sun on the beautiful coasts of Greece simply because we were Americans who happened to have Greek ancestors. I was flown here from New York for free, to soak up my culture and language, while mothers, fathers and children were forced to leave their homes, fight to survive the dangerous trip across the ocean, and arrive in land which became their detention center for the foreseeable future.

The weight of this moment struck me a bit later, when this jarring inequality ignited my interest in working with refugees. My Yiayia may now have Alzheimer's, but I live as her memory, an extension of her. I promised myself that I would go back to Greece the next summer, not to relax on beaches, but to serve people who arrived on my grandma’s island the way she left her homeland — as a refugee.

That’s how I spent last summer: volunteer-teaching refugee children English and music on my Yiayia’s island, with a Greek nonprofit called METAdrasi. Over a summer crammed full of frustrations and joys, I would think of my grandma’s words often. Like when a local builder told me I should not work for refugees because they should be pushed back into the ocean to drown. And when my distant relative rescinded her offer for me to stay at her empty apartment when she heard I was volunteering for refugees.

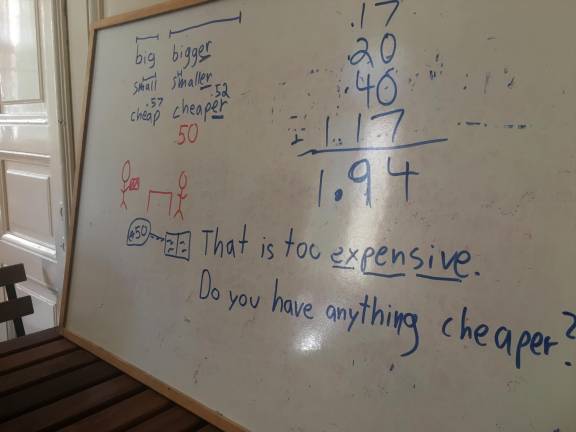

On my first day as the group’s first long-term volunteer on Chios, I found myself in a storage container repurposed as a classroom, where 20 kids from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq were screaming in Arabic, Kurdish and Farsi. I was told to teach.

It was harder than I’d imagined. A small boy regularly pointed to me saying “no good, no good” and spit on another child, as I heard his parents sometimes did during disputes about food distribution. A poorly fed girl woke from a complete daze after I shook her shoulders during our lesson counting chairs. An 8-year-old, who got into fist fights about twice a week, was found in the center of town, alone, at 5 a.m. one Wednesday morning, miles away from the refugee camp.

It was hopeful, too. A young father who walked his 6-year-old son to class every morning asked me when they were going to learn how to write paragraphs. A 12-year-old found me every lunchtime to eagerly hear me read. She was patient as I fumbled with pages stuck together with dried, pink frosting left from another kid’s sugary breakfast. We sat on the old couch and she stared at my lips as I read, which I learned was because of the damage bombs left on her ears. A 14-year-old became the first person in his family to read a book in any language. A young unaccompanied boy thanked me for sharing meals with the group. It was, he told me, the first time a volunteer sat and ate with them. And a 21-year-old Greek American got an education.