The epic journey home

A family’s years-long quest to figure out where in this wide world to settle down

Look up the word “home” in the dictionary and you’ll find 31 different definitions. There are the nouns: the obvious house or apartment, any place where one’s “domestic affections” are centered, an animal’s lair, any place of residence or refuge, a person’s native place or country, a base of operations. In games it is the destination or goal, such as home plate. “Home” can take on a descriptive mantle, meaning principal, main, reaching the mark aimed at, deep to the heart. As an action word: to home in, to go home – that is, to a place of familiarity, ease, proficiency and freedom. Home is an expansive concept whose girth allows for tailoring to an individual’s own understanding and needs. But finding your way there is not as straightforward a proposition as it once was.

It has been a long time since home meant the place where you were raised. Seventy percent of college students go to a school that’s at least two hours away from where they grew up, and according to census data, three quarters of those graduates quickly move again at least once. Job opportunities pull people further and further away from the places they used to call home. Remote access to jobs these days also gives a new wave of people the freedom to choose where they live for reasons other than work, birthing whole movements of those who are uninterested in grounding themselves anywhere.

Leaving home, even for just a year, can change your relationship to it forever. It takes on something familiar yet slightly foreign, like an ex you once loved. With the new distance, comes an exotic sort of emptiness that can be filled with something unknown. Something that you must search for. This is the search that Matt and Rebecca Burns have been on for years.

But first, they had to meet. Rebecca’s parents, having in their own time undertaken a search for home much as their daughter would, settled on Portland, Oregon, where Rebecca spent most of her adolescence. When it was time for college she made her way to NYU to study 21st century education. While walking in Brooklyn with friends, one of them spotted Matt on the street and stopped to say hi. Within a half hour, Matt and Rebecca were drinking champagne and conversing in French.

After eight years in New York City together, the couple decided to have a singular wedding in South Dakota, where Matt is from. The venue: a horse sanctuary on native Lakota land. Taking a page from Lakota custom, Rebecca went out to hunt a bison with a good friend, whose meat would feed their 150 guests, and whose pelt, which they named Freedom, they still carry with them as bedding.

Not long after the wedding, Rebecca was hired to teach experiential education in Asia and Africa. Matt moved to Los Angeles to pursue his acting career. After two years, Rebecca came back to the States to join Matt in L.A. She got a job in high end hospitality and a couple of years after that, they got pregnant.

The new family of three tried to find their footing in the city. Rebecca had a full schedule at a job that was very different from the fulfilling work she had been doing overseas. Matt took over primary care of baby Anouk, trying to juggle parental responsibilities with his own acting career. It felt like a real struggle to both of them.

They questioned whether Los Angeles or New York were where they wanted to settle – cities where, as Rebecca put it, “You can buy a s***hole for $1.5 million.”

Becoming a parent has a way of making you examine your priorities. For Rebecca and Matt, a new awareness was emerging of how they were leading their lives: how they were making money, where their energy was going, and where they wanted it to go. You start to notice the things that are in conflict with your best self.

“It all has to align,” says Rebecca. For them, it was not.

Then Anouk tested positive for exposure to lead, and all of a sudden, the routine that was starting to feel like a rut gave way. They had to move out of their house for a while. They took the savings they had and for what was supposed to be four months, decided to road trip, camp and regroup.

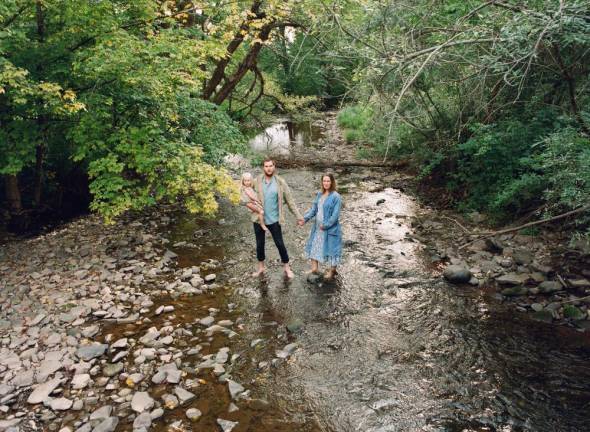

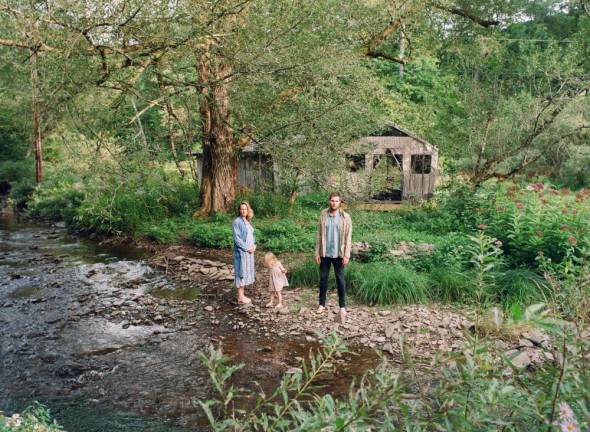

Two years later and counting, their four-month journey has become a quest that makes even the most adventurous among us feel exposed as pallid suburbanites. Pitching tents in national forests, baby in tow, they have coursed through Northern California onto the Southwest. Did a stint in Taos and then went up through Colorado to the heartland. They stayed a couple of weeks in Minneapolis visiting family, then on through the Great Lakes and up into Canada. In the summer of 2018 they dipped back down into the Catskills, where Rebecca’s friend owns The Mystic Lodge, an old dairy farm with four furnished tipis in the pastures.

They decided to stay the summer. Their savings were dwindling, and here was an opportunity to stay put, make a little money and visit with friends. They traded their tent in for a tipi and built an outdoor kitchen. Rebecca worked at a friend’s pop-up restaurant and Matt helped a local man build straw bale homes. They still had not found what felt like home. What they had found, it turned out, was a hot-button, even among friends.

“People judge it,” said Matt. “Right now we’re living outside of the rules and there are a lot of people who have a strong reaction to it.”

Our cultural norms primarily dictate that we work, make money and “succeed.” People who chart their own course like Matt and Rebecca can’t help but seize our attention and become the subject of our private speculations – which tend to fall into one of two camps. Camp one is that they are irresponsible. Camp two is epic romanticization.

Folks tend to make one of two opposing economic assumptions as well: either that tehy are rich trustafarian types, or a hobo-vagabond-gypsy family. It can be hard to wrap your head around the idea that people like you would choose such an extreme lifestyle.

There is a reason that most people have a more-or-less fixed address. Being rootless isn’t an easy way to live, and maybe quadrupley so with a baby. First, it’s quite isolating. As social as you may be, and as many people as you might meet along the way, until you take root, they are all temporary. The only thing you are tethered to on the road is each other. And your car. If you don’t have an overflowing stack of cash to mess around with, then you will be forced to constantly keep tabs on how fast it’s all going out and when is too late to stop and replenish, and will it be that simple to find work to replenish in a town and amongst people you don’t know? It requires an ironclad belief in both your resilience and the world at large. Coming up on two years, it has taken a toll.

Rebecca has always felt most at one with herself in the wild. “I have been most surprised about how anxious I have felt since living this way,” she said. As she settles into her new role as a mother, “I have come to realize that I need stability in order to be present.” Matt has not suffered this stress. If anything, he speaks of his experiences over the past couple of years in a way that makes it sound as if he has been empowered by them. He has pride in how they have been able to make it work thus far, a solid belief in their ability to continue as such. They both still have a certainty in the lamplight of what they are searching for. It’s just that only one of them is stressed by the process.

These years have not been without real trials for the Burns family. Living in a tipi in the Catskills, Matt got Lyme, culminating in tingling numbness so severe that they wondered whether he had multiple sclerosis. On the heels of that, there was an emergency in Rebecca’s family that required her and Anouk to fly out to Turkey at a moment’s notice, and stay there for the rest of the winter before coming back to the States in the spring. A pretty solid plan to go back to Taos and give it a go got sideswiped by family obligations in the Northeast, and they found themselves back in the Catskills for another summer.

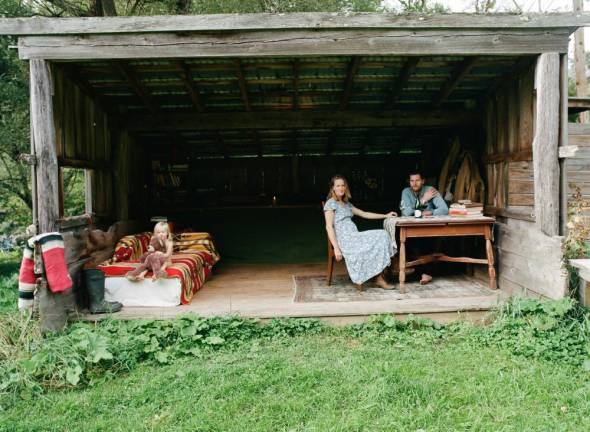

This time, they had an idea: they would host outdoor dinners on their friend's property called The Sweep. They built a platform on his pasture next to a horse barn, borrowed a friend’s prospector tent to pitch as a bedroom and used the horse barn as a living area. They built a clay oven outside to cook open-fire meals for their community, their neighbors – like me and my young daughter, who became regulars at their “family meals.” Depending on the cost of what they were cooking, they would charge people anywhere between ten dollars for wood fired pizzas to thirty per seat for meals served in courses at tables.

Atop a grassy hill, with a view of the valley below and the mountains beyond, people came most weekends over this past summer to be fed. Some meals were served at proper tables set in the grass, but some of our favorites were ordered by a counter at the clay oven, where you would collect it when it was done and sit on a blanket or in the grass. There would be lots of people you knew, as well as lots of weekend vacationers you didn’t know but got to know. There were natural wines for sale from Fifi’s Import, an independent importer of biodynamic and “living” wines from around the world, with Fifi present to taste and serve. Every dinner wound down with a sunset and a bonfire, and eventually the stars. Sometimes it would be a manageable 30-ish people, and other times, many many more. They would keep making food until it ran out.

“Food is love,” said Rebecca. Which reminded me of a memoir I read, whose author counseled that you should never trust anyone who doesn’t cook because cooking for others is such a pure act of generosity. These dinners were a summer gathering place and more: a place of refuge in the open air to commune, unwind, connect. On their wedding anniversary weekend they served a bison tagine.

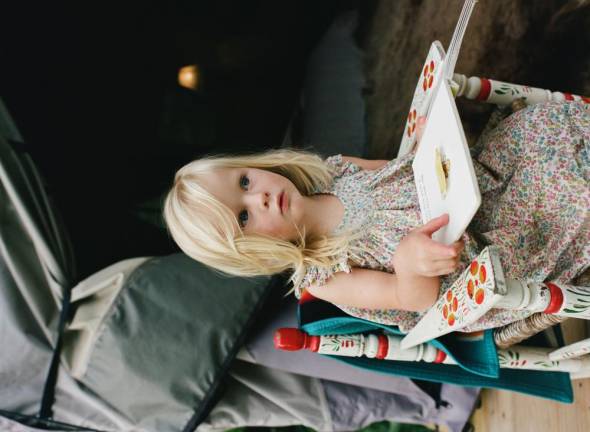

And then there is Anouk. Something that they wholeheartedly agree on is that this hunt has been the best thing they could have done for her. Now two and a half, Anouk is more comfortable sleeping in a tent than a bed. She is an unabashed free spirit, a little girl with a comfort and affinity with the wild, the dark, animals, fire – things that increasingly seem primitive to those who don’t seek them out. She is a master of squatting to pee outside.

The curiosity and self-sufficiency that I observe in her make Anouk seem years older than she is. She is now at an age where the concept of home is a curious thing to her. At two and a half she has started going on play dates at friends’ “homes.” Hearing her mother tell her she’s going to play at Ramona’s house, or Aislin’s or Pepper’s, she has begun to ask, “What’s my home?” Rebecca told me that during their stint in Turkey, she was starting to get migraines from breastfeeding. Her body was telling her that it was worn out. Part of what made it so hard to wean her baby was that she felt like her physical body was Anouk’s home, more than anything else. These days, Rebecca and Matt tell her that home is wherever they all are together.

It is now two months since I interviewed them. Six months after I first befriended them – and they have already gone. Rebecca had in recent months found out that she is pregnant again. Her friends, myself among them, expected that they would take root here, at least until after the birth, but a month ago I was picking up my daughter from preschool when I heard Rebecca call out from behind me.

“Laura! Laura!!” I turned around to her smiling wide with a handful of stuff she was donating to a church.

“I’m so glad I ran into you! We’re leaving! I just wanted to say goodbye.” She laughed a buoyant laugh, “I know. We’re crazy,” she said. It was a Thursday morning. They left two days later.

They are missed here. “It’s too much of a heartbreaker to get close to the nomads,” said one of our mutual friends.

I follow their posts and documentation of their journey on Instagram and they seem excited, and happy. They are onto new adventures and continuing their search. Recently I talked to Rebecca on the phone. “So is Portland it?” I asked her. “Have you found it? Are you rooting?”

“It’s like following a trail of bread crumbs,” she said. “We’re always getting closer."