Coop dreams

The backyard flock’s historic comeback meets its match: apprehensive neighbors

Time was, frugal American households kept a backyard flock for eggs and the occasional Sunday chicken dinner. “In time of peace a profitable recreation, in time of war a patriotic duty,” exhorts a 1918 government poster, urging two hens in the backyard for each family member. In farm households in the early 1900s, women’s income was often called “egg money” because it often came from selling excess eggs – one of the oldest of side hustles.

This spring, in what felt like a blast from the past, the government once again encouraged Americans to keep laying hens in response to the skyrocketing price of eggs. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollin, who keeps chickens herself, said in March, “People are sort of looking around thinking, wow, maybe I could get a chicken in my backyard.”

The idea quickly turned into yet another political lightning rod, but there’s no debating one thing: keeping chickens is indeed back in fashion. In 2024, 11 million American households owned backyard chickens, a 28 percent increase from the previous year and nearly twice as many as in 2018, according to the American Pet Products Association.

“People are getting more [chicks], but it’s been since Covid too – that’s when it really started,” said an employee of Wadesons in Warwick, NY, which had sold out of chicks by May 1. “A lot of ’em are new, you can tell, just by them not knowing much about it.”

At Tractor Supply in Chester, NY on a Friday in May, longtime employee Gene Latham was packing up six chicks for a family expanding its existing flock. Tractor Supply had been selling out of chicks within 24 hours of receiving a shipment, said Latham. “People think they can raise ’em cheaper than what they can get at the store,” he said.

They’re not wrong, said Latham — but half the chicks that leave Tractor Supply won’t live long enough to lay an egg. “People don’t know what they’re doing. They have to be taken care of twice a day,” a lifestyle change many aren’t, in the end, willing to make.

If you’re handy, thrifty and committed, though, you can absolutely raise eggs that are cheaper and vastly superior to store-bought. Just crack an egg into a pan to see the difference: home-raised eggs are not only a richer hue of taxi-cab yellow but also hold their shape, said Latham, a testament to their quality.

‘A profitable recreation’

Gilda Burke, a home baker with 23 chickens on her 2.6-acre Warwick property overlooking the Pochuck River, is part of the modern renaissance of backyard flocksters. She started keeping chickens four years ago, the last time the price of eggs spiked thanks to bird flu. When a flat of eggs went from $4.50 to $14, “I was like wait a minute, let’s pump the brakes here,” she recalled. Her dad had kept chickens in Miami, where she grew up. “I knew they weren’t a lot of work. So I was like, let’s just try six and see how it goes,” said Burke, mother of two teenagers, whose husband is an FDNY fire chief.

There’s a meme, she jokes, that says “I was born with a how-hard-can-it-be gene.’” She was blessed with that gene. Burke taught herself how to use power tools when her family moved into their house seven years ago. Notwithstanding a couple mangled fingers requiring surgical reconstruction, she remains confident in the amateur construction department.

With instruction from YouTube, she built her coop for a relatively frugal $850 in raw materials, complete with a solar-powered door that lets her birds in at dusk and out at dawn. These days, her flock lays up to 18 eggs a day, most of which she sells – at the throwback price of $5 a dozen – to people who responded to a social media post she put up on a Warwick parents’ page. She got so much response from that single post that she has a waiting list 15 deep.

Burke, who caters weddings and birthday parties as the one-woman Scratch Baking Company, will go through a dozen or two of her flock’s eggs each time she bakes.

“They also eat all the ticks in the yard, which is a huge plus,” she said.

Having lost two-thirds of her flock to hawks, foxes and raccoons, Burke is adding a covered run (which put her back an additional $600 in materials) and only lets the chickens free-range when someone’s outside with them. “They have their personalities and it’s calming just to sit outside and watch them free range for a bit,” she said.

Burke is thrifty, particularly when she’s not working full-time, and all her chicken infrastructure is DIY. She made her own feeder and waterer out of five-gallon buckets and constructed the wooden farm stand where, when it’s not too windy, she puts out baked goods or eggs for sale. Old feed bags serve as a protective lining on the coop walls and floor, and a kiddie pool as a frugal alternative to a second waterer.

If a penny saved at the grocery store is a penny earned, Burke is earning about $276 a year by our back-of-napkin calculations — not quit your day-job numbers but reliable “egg money” all the same. At this rate, it will take her five years to recoup what she spent on the coop and run. But like Burke, most of the 23 local chicken keepers Dirt surveyed are loathe to charge their neighbors market rate.

Also cutting into her bottom line is her flock’s high mortality rate – the downside of free-ranging – and the fact that, like most survey respondents, she lets her birds live out their natural lives. That means less productive layers and no stewing hens, but also allows for more pet-like relationships between humans and birds.

The margins may be slim, but Burke hasn’t looked back since bringing those first six chicks home from Tractor Supply. “I didn’t do it to make money,” she said. “I did it because I wanted the eggs.”

‘The dream is the agrihood’

Seven miles away, in the Village of Warwick, Burke’s neighbors had visions of a scaled-down version of this scene when they moved here from Queens three years ago. They’d assumed they would have maybe six chickens on their half-acre homestead, providing manure for their vegetable gardens, compost turning, tick control, education for their young daughters and of course, fresh eggs. After all, their neighbors in Astoria kept chickens, where it was perfectly legal, as did family in Long Island.

But upon landing on their half-acre lot near the hospital, Tony and Angela Cornelius discovered that, in this community that was otherwise so welcoming, a 1976 village ordinance prevented the “keeping of fowl, rabbits and pigeons” within village limits. Orange County may be renowned for its agricultural heritage, but only some of its villages (Chester and Monroe) allow backyard chickens; Warwick and Otisville do not.

“One of our daughters, her favorite thing is an egg sandwich. In the morning, I wanted her to be able to go out and pick her own egg,” said Tony, president of Lively Plant Systems, a company that installs living walls.

“Ticks are the bane of living in the Hudson Valley,” added Angela, who works in real estate. In the thick of farm country, it’s hard to even find local eggs, the couple said, with farm stands getting picked clean by city folk. When they do find eggs, said Tony, “we get the inflated city price.”

Sure, the Corneliuses could have quietly gotten a few hens and kept them under the radar, as more than a few village residents do. But they didn’t want to risk having to give them up if a neighbor complained. They also want this change to be broader than themselves.

Nearly half a century since the passage of the village ban on fowl, the pro-chicken contingent is confident that the moment for change has come. “Oh, it’ll happen,” said Tony. In a month, 110 people signed a petition to allow backyard chickens in Warwick, most of them village residents. “If we can get some of those people to show up at a meeting, how could it not pass?”

Change is, after all, in the air. Andover Township, NJ voted last year to allow residents to keep up to eight hens, after paying a $15 annual fee and taking a mandatory class. In Milford Borough, PA, where fowl are allowed only on properties of at least five acres, a nine-year-old girl challenged that ordinance in September. (One survey respondent copped to raising seven free-range hens on an acre in Milford.)

“The dream is the agrihood,” said Angela. “I want chickens here, gardens there. I want to be able to share.”

“This is a great way to bring together community,” said software engineer Brian Torpie, who met the Corneliuses through the campaign to lift the village ban. “When you get this age, you need shared interests,” said Torpie, also a parent of young kids. “Otherwise, I just want to be left alone,” he laughed.

Torpie got yard signs made and researched what other villages have done about backyard chickens. He found three recurring guidelines: the property has to be a certain size, the birds have to be enclosed, and the set-up has to be inspected.

The Torpie household makes its own bread and buys organic food, and is eager to get a few hens. “I don’t want to go full farmer; I’m a tech guy. But at least give me that,” said Torpie, adding: “Eggs are the perfect food, like God’s creation – everything you need in there.”

After doing his research, Torpie concluded that “a lot of the objections people have are just wrong,” like worries about smell, bird flu and noise. “They don’t make much noise. I think the local birds make a heck of a lot more,” he said. (Roosters, of course, would be a hard no.) “We can find a nice balance between keeping the aesthetic rural, but yet, still a village with a hospital and a CVS.”

“And one Burger King,” laughed Tony.

‘Yuck’ factor proves persistent

But these apprehensions turn out to be persistent. A 2011 effort to lift the village ban fizzled in the face of “public concern about cleanliness, health, noise, small lot size,” said Mayor Michael Newhard. “We are looking at this carefully as many of the same concerns from residents remain. We’ve reached out to Cornell Cooperative for guidance.”

An anonymous poster on a Warwick parents’ page said they don’t spend $25,000 in property taxes to live near chickens. Others worry about attracting vermin and predators like coyotes, foxes and even wolves, said Newhard.

“Keeping vermin like mice and rats away is virtually impossible,” said Renee Layman, a vet tech who lives in Cochecton, NY where she keeps 37 chickens, and works in Warwick. Chickens also attract foxes, raccoons, opossums, bears and “your neighbor’s outdoor cats as well as strays,” she said. A former Warwick resident, Layman doesn’t think chickens belong in the village. “You’re going to find neighbors pitted against neighbors,” she said.

Torpie and the Corneliuses say the vast majority of people they talk to about overturning the chicken ban have been warm to the idea, whether or not they’re interested in keeping hens themselves. But Newhard reports that most of the comments he’s gotten are against.

A Village task force to investigate the backyard fowl question, chaired by Village Trustee Barry Cheney, will begin to meet in September. The committee will consult with Cornell Cooperative Extenion and Suzyn Baron from the Warwick Animal Shelter, said Mayor Newhard. “There is a survey planned for residential input as well. The task force findings will be brought to the Village Board,” said Newhard.

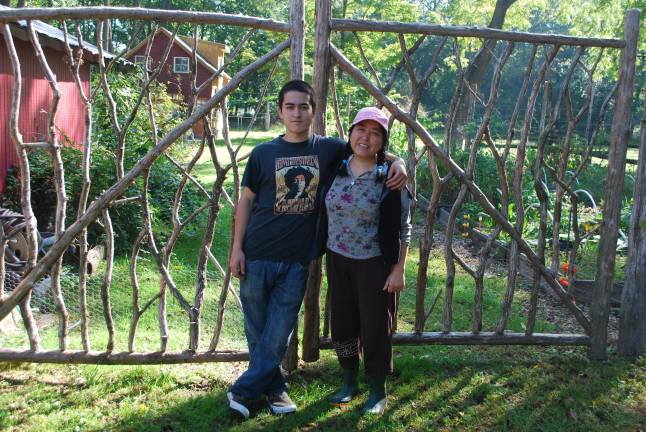

Perhaps the most veteran foot soldier of this struggle is Raphael Cox, 32. Cox challenged the fowl ban in 2011, as a teenager. He and his mom, accountant Nancy Peng, had been keeping six hens on their three-quarter-acre property, enclosed in a colorful chicken tractor within their extensive vegetable garden, when a neighbor complained. She was concerned chickens would lower her property value. Cox, then 18, requested a waiver to the ordinance, sparking lively debate but ultimately, no dice. The village did, however, hammer out about half the backyard chicken legislation back then, said Torpie.

The intervening years have developed Cox’s philosophical streak. “A chicken can outperform any machine man creates, we just don’t fully acknowledge how advanced it really is,” he said.

Cox plans to get hens again the moment the ban is lifted. “I’ve had the best fruit production when I’ve had chickens off my fruit trees: less bugs, better fruit,” he said. Chickens are only part of his homestead vision, which also includes fish.

“I think I can have bees,” he said with a shrug, “which seems to me more dangerous?”

Of the 23 local backyard chicken keepers we surveyed, the average flockster: