Cracking open deep time

SUNY Orange students unearth ancient ocean life

“I heard there’s gonna be fossils,” said Gavin Gartocki, 19, of Pine Bush, on his way into the science hall at SUNY Orange on a Friday afternoon. Like most of the 21 students who showed up for geology club on March 28, Gartocki is not a geology major – he’s studying liberal arts. But the opportunity to eat pizza and help break open a 400-million-year-old boulder whose surface teems with fossils was a draw for students and even a few professors, who stopped in after the week’s classes had wrapped.

Minutes later, Daniel Grant pulled up to the science hall and opened the trunk of his Dodge Caravan to reveal the 93-pound “Big One.” Grant, an amateur fossil hunter and professional sculptor, had found it a decade and a half earlier atop a rock wall in his Westtown, NY backyard. It was thickly etched with signs of strange, ancient life: shells, corals, trilobites.“I’ve been wanting to do this for 15 years. It just kind of sat there,” said Grant. “Ninety-five percent of what is in a fossil is hidden inside. I wanted to wait until I’d have a professional paleontologist witnessing and explaining whatever surprises lurk.”

The man in question, Geology Professor Anthony Soricelli, loaded the Big One from Grant’s van onto a hand truck, along with seven boxes of smaller fossils Grant had also collected over the years. Soricelli had had a long week, including a tenure meeting that day. Didn’t the spry 20-ish-year-old students think they should help? this reporter asked, getting only laughs.

Soricelli pulled the hand truck into an elevator, upstairs to his classroom, and heaved the Big One onto a lab table, where students gathered round.

“We have some big bio going on in here,” said Brianna Reid, 30, of Middletown, a natural science and math major. Using the straight end of a plastic spoon as a pointer, she indicated something that looked like the ribs of an early fish, but might also – Biology Professor Walter Jahn suggested – have been the track of an ancient marine invertebrate like a sea pen.

Grant pointed out the hole in the middle, where a squirrel had been stashing nuts when he found the boulder, as he helped himself to a slice of pizza. Eventually, the anticipation was too much.

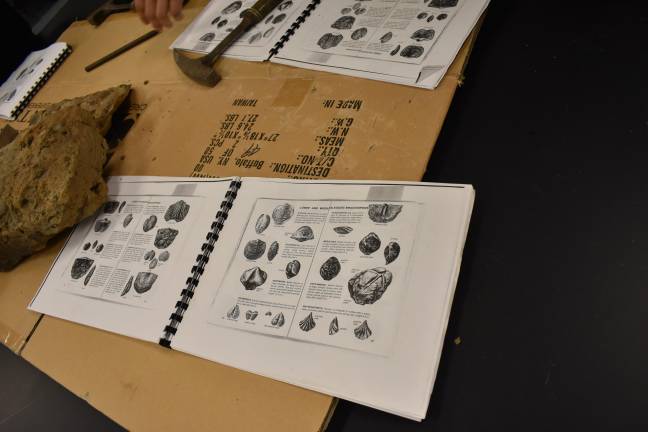

“Daniel, we’re all afraid to hit it, so you should start,” said John Wolbeck, chair of the Science, Engineering and Architecture Department. Grant positioned a chisel and did the honors, whacking the chisel with his mallet until a sizeable chunk of rock broke off. The rock’s interior was reddish, surprisingly damp and soft, packed with countless imprints of small corals, trilobites, brachiopod shells and moss animals called Fenestella that formed fan-like colonies. Grant pulled aside a mess of “modern stuff” – spider webs and leaf litter – and got to work. As chunks broke off, he passed them around to students, who took over whacking at them, timidly at first.

“I don’t know how to chip away at anything,” said a young woman, examining her chunk, which was laid out on an empty pizza box. “We’re engineers, not geologists, bro.” But she and her partner quickly got into it, employing faux British accents to narrate their finds.

The fossils coming out of the Big One had accumulated between 485 and 359 million years ago, Soricelli estimated, when our region was located near present-day Florida and deep at the bottom of an ocean. That meant they were all about twice as old as the oldest dinosaur, yet their intricately geometrical details were as finely etched as a piece of jewelry. For the next hour and a half, the room echoed with clanging chisels and the occasional excited announcement: “We got action, baby”; “Break it, break it.”

“It’s a good thing we did this at 3 on a Friday,” said Soricelli, alluding to the racket. The campus had emptied out for the weekend and the science hall was deserted but for this gathering. “There’s no way this would go over.”

For two hours, students chipped away at their chunks, occasionally videoing each other “for the ‘gram” (that’s Instagram; yes I had to look it up). Pieces of rock flew across the room. Fossils were crushed in the process of enthusiastic amateur excavation, eliciting a resigned shrug from Soricelli.

Meanwhile, Grant kept working on the Big One, which had begun resisting his efforts to crack it open. After getting through the sediment comprising the first third of the rock, he found himself up against a far harder stone that “felt like peeling a hard giant avocado. It took me most of the meeting before I started, slowly, to realize I had to give up trying to crack it,” he said. (When he got home, Grant ordered a pneumatic air scribe to help him excavate the boulder’s core.)

But the chunks that did come off the Big One that Friday turned out to contain some breathtaking finds, like a couple horned-shaped corals called Streptelasma, a genus of corals that went extinct 359 million years ago. On my walk back to my car, I fingered the fossil in my pocket which, with Grant’s blessing, I’d taken home as a souvenir. It was a double-sided fossil: as Grant had shown me a trilobite on one side, I’d noticed on the other the radiating pattern I’d just been admiring in the fossil ID book that resembled a flowing ball gown: a Fenestella. I ran my thumb over the mesh indentations left behind by a moss animal colony that lived when fish were the planet’s most advanced form of life.

There were so many fossils in this one rock. How many more rocks like it were out there, fossilized in the black dirt? That was what Soricelli found himself wondering in the aftermath of that memorable geology club meeting. Grant had found a single piece of seabed, but the whole ocean floor would have been covered with these little shells. “Think of a bunch of clams just dying and the shells just piling up,” said Soricelli. For millions upon millions of years.

Grant’s yard, noted Soricelli, was clearly a rich fossil hunting ground. “I may have to ask to take a visit.”