What’s under Warwick?

It all started in 2013 when Jim Turner, an archeologist who volunteers for the Warwick Historical Society’s day camp, directed a group of fourth graders to dig in a random spot behind the 1764 Shingle House. They were hunting for the occasional goodies that sometimes turn up in the yards of very old houses — bottles, pieces of broken pottery. They hit brick, curiously curved and arranged in a circular herringbone pattern. A patio?

Turner, who lives half a mile from the site, stayed behind to examine the thing. What they had happened upon was a cistern six feet in diameter, for catching and holding rainwater.

The next spring, volunteers from the historical society came to finish digging out the cistern, mostly to see if there might be archeological treasure at the bottom. It was the first hot day of May 2014, and the two diggers’ ages averaged 76. Now he knows she can throw buckets of dirt around all day, but at the time George Knight, 71, a volunteer from the archives department, wasn’t sure about the stamina of his digging partner, Dot Zwerin, who’s 82 and usually volunteers in the costumes department. So when the sun started beating down he proposed they stop digging the cistern and, while waiting for the shade to come around the house, dig in the shade next to the house — again, a random spot.

This time they hit stone. Its wavy pattern was a head scratcher; what did it signify? Knight went back to the society’s offices across the street, bringing a fellow archives junky to look at what they’d just uncovered. At the same moment they both had the same thought: this stone stood upon more stone, which had crumbled over time. What they had found was the top of a stone wall.

It had to be a wall of the house, Knight became convinced, the one mentioned in the journal of “Rocking Chair Benny Sayre.” Sayre, who lived from 1865 to 1940, was the keeper of Baird’s Tavern across the street. He earned his nickname because he liked to rock on his porch and shoot the breeze with passersby, recording the gossip in his journals. “But it’s all gone now,” Sayre had written, cryptically, of the little house.

If this was the house of legend, it would measure 15 feet by 20 feet. So far, it seems to.

“In most legends there is a kernel of truth. And that’s what we’ve got here. Except we’ve got more than a kernel,” Knight said.

Knight is quick to point out that he’s not a professional archeologist, but a retired businessman dabbling in archeology. (There’s no money to pay a pro to do half the things the society wants to do, let alone an exploratory dig. The $250,000 state grant that has this place buzzing is for keeping the Shingle House standing, not excavating the backyard.)

“Where I don’t have a background is interpreting all the things we see,” said Knight. It sounds hokey, he knows, but “sometimes you just stand here and try to listen to the stone.”

Notwithstanding his lack of a degree, “I think he’s doing very careful work,” said Dr. Richard Hull, Warwick town historian. “The evidence seems to be mounting that this could be the blockhouse that has been described in earlier writing by Benjamin Sayre.

“I can see he’s having a lot of fun,” said Hull. “It is rather tantalizing.”

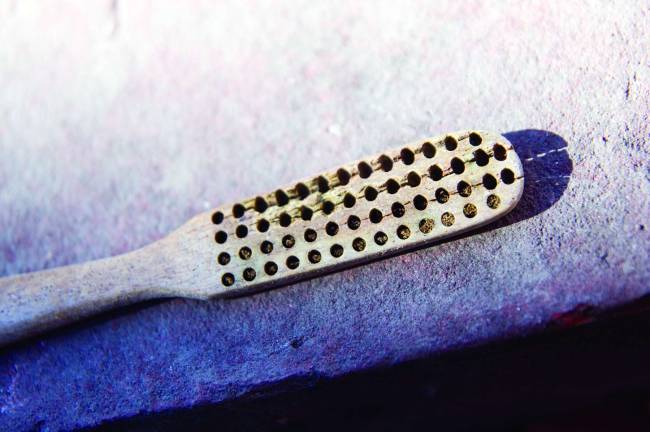

Three houses in from the Mobil Station, half a block from the library, another world is emerging. Remnants of a settler family’s life are coming out of the ground faster than they can be bagged and tagged: clay pipe stems stained by smoke, a celluloid toothbrush whose holes once held boar bristles, a child’s broken alphabet dish and doll, mussel shells and vials upon vials that held the anti-depressant du jour, “elixir of opium.” But the biggest find is still underground: the blockhouse.

Cryptic the little house remains, with questions coming up as fast as booty. Why was it buried? Where did all the dirt come from — perhaps from when they dug out the village roads? And what was it? Slave quarters or a summer kitchen? A temporary place to live while the Burt family built the main house, or a defense against Indians? All of the above?

“It could have doubled for several purposes,” said Hull. “It could be a blockhouse” — a defensive structure or fort. “It could have been built during the French-Indian war,” fought between 1754 and 1763. “Just about the time when the Indians and the French were allying against the British, there was the worry that they had power in upstate New York with the Iroquois, and there was always that danger that they’d swoop down and come right into the Hudson River Valley.”

The excavation is still in its early stages, but even “if it’s not exactly what they think, it’s probably something from that period,” said Turner. The stone construction suggests “a place to retreat to, to protect themselves against Indian attacks.” An outpost in the backyard is “obviously indicative of a pretty volatile kind of environment that these people were settling in.”

Before digging, Knight marks the area with a grid so they know within three feet wide and four inches deep where everything came from. Zwerin then sifts the dirt through a quarter-inch screen and places any finds in a two-gallon bucket with a piece of paper noting the grid section. When Knight gets down to “Colonial level,” they will move to an eighth-inch screen or even finer, he said, “because you don’t want to miss anything.”

Knight’s own house is now overrun by artifacts that he’s in the process of cleaning and recording, according to his wife, who stopped by around lunchtime. She was running errands that he might have taken care of before his obsession took hold.

appeared to have been hidden, wedged between rocks in the ash pit that was probably used as a trash heap.

“Warwick back in the day was higher than a kite,” said Knight. So it seems. These little bottles were considered medicine, that, not unlike today’s Oxycontin, turned out to have a serious drawback.

“We had a substance abuse problem here over 100 years ago,” said Hull. “In the 1890s up until World War I, there’d be itinerant merchants who’d come into town to sell elixirs to relieve pain, headaches, relieve depression and so forth. They spiked these concoctions, so that when they sold them people became quite addicted in some cases,” he said. The Women’s Temperance League may have been a response not only to alcohol abuse, but also to these un-talked-of habits.

Opium back then was a household remedy prescribed for everything from teething to amputations. Hull’s sense, gleaned from snatches of oral history, is that while by no means restricted to one group, opium addiction was particularly rife among older housewives suffering from things like arthritis, dyspepsia – ailments that nag later in life.

“When my kids were little we used paregoric on their gums,” Zwerin said philosophically. Paregoric is yet another opium tincture. “Life was hard. That’s what they did.”

Everyone likes to ogle the opium bottles. They’re scintillating in a way that stone walls just aren’t. That bugs Knight, although he’s good natured about it.

“Dot is very finds-oriented. I’m finding a building and because it won’t go through a sieve she’s not interested,” he stage-whispers. “Our reward isn’t the little bottles. The purpose of those is to date the big building.”

The blockhouse, or whatever is emerging from the dirt, will fit right into the historic society’s “campus” that’s coming together on Forester Ave. – it includes the 110-year-old Union African Methodist Episcopal Church that was picked up and moved to the site next door, the Shingle House and its barn, the Buckbee Center across the street, and Baird’s Tavern a stone’s throw away.

The historic society wasn’t always this go-go-go. “As you can imagine, it was very dry,” said President Mark Kurtz, who stopped by the dig. “There’s become excitement, with the kids that visit.” Every fourth grader in the Warwick school district takes a tour every year, and the middle school just launched a Sustainable Architecture class that will be taking a field trip to the historic society’s properties.

“We’re starting a bunch of brand new reach outs to the school district,” he said. “The point is to make this history become important to people, and that’s the time to reach them.”

The society’s new director, Lisa-Ann Weisbrod, stopped by with her mug of tea. The society’s only full-time employee, she’d been there just five weeks.

“It’s amazing how much is going on,” she shook her head. “It’s a historical society,” she thought when she took the job. “How busy can it be? It’s crazy.”

She had to run back to her office and lock the door to finish a grant seeking money to put an extension on the back of the church, as well as climate control so that it can host exhibits, including a permanent one of 16 panels depicting African American history in the valley. Weisbrod envisions the dug-out blockhouse being fitted out with a Grand Canyon-esque viewing platform and signage, so visitors can walk over it and look down into the house.

The little fortress by the Mobil Station could have a lot to teach all of us. Knight wonders whether the inhabitants cleaned the place out before they buried it, or just pushed the roof in over a house full of – who knows what? During the Shingle House’s renovation, it yielded up not only rare coins like a 1779 Spanish real minted in Mexico City, but also evidence of a superstitious bent: a worn and frequently cobbled child’s shoe in the chimney, placed there to ward away evil spirits; a haypenny placed where two roof beams met.

Regardless of what’s inside, the existence of the blockhouse would be a revelation in and of itself. “If it is a blockhouse, it sheds some new light on our history, but it also has contemporary parallels,” said Hull. “We’ve all been somewhat traumatized by events in Paris, Brussels, Mali,” he said, referring to the terrorist attacks by the Islamic State. “People are a little frightened,” although the chance of jihadists targeting Warwick today is as remote as Indians swooping in with tomahawks was in Colonial days.

Fear (like opium) has been a recurring element of our history, one that often gets overlooked in the glow of hindsight.

The blockhouse – which Hull envisions restored, one day – could serve as an example of how people react to threats to their safety, real or perceived, and stand testament to one aspect of America’s story that we might otherwise forget.