Starting fresh

It’s Saturday, so Delia Ruckdeschel is baking baguettes and granola that she will sell later today at a raw milk farm in the next town over.

On a whiteboard hanging on the door to the mud room is a quote from Proverbs: “In much work there shall be abundance. But where there are many words there is oftentimes want.” Maybe that’s Delia’s way of telling her five kids, ages three to 13: leave mom alone, she’s baking. The kids, two of them playing a board game in the living room, appear to get the message.

This side business, called Alpine Hill Baking, was born little by little. Delia noticed that the tortillas at the grocery store “were filled with junk” to extend shelf life, “and they don’t have to be,” she said. If they were produced and consumed locally, in other words, then shelf life wouldn’t be an issue. Delia knows tortillas. Her mom grew up in Mexico, making them every day.

So she and her husband Chris Ruckdeschel – who liked experimenting with sourdough – knew what they had to do: make all the family’s breadstuffs themselves. They invested in a high quality USA-made wheat grinder. They started buying organic wheat berries in 50-pound bags from a natural food co-op, grinding the wheat berries the day of baking so the bread was at its freshest and most nutritious. Delia got good feedback from friends on her bread (“nutty, complex”). They had their tap water tested, registered with the state, and in May 2013 Delia started selling her bread at Freedom Hill Farm in Otisville. It sold well. Delia added granola made with organic coconut oil and local honey, and that sold even better. “It started with bread. Now people are really excited about granola. I don’t know – very slowly it expanded a little bit,” said Delia, 36.

Alpine Hill Baking brings in a bit of money, but more than that, it dovetails with the family’s faith, which is centered on being productive and being good stewards. “If it were me seven years ago, I would have bought it too,” said Delia. “I feel like I’m providing something around here there isn’t. I challenge people to find a healthier bread in Mount Hope.” She laughs her big laugh. “Which is silly.” (There’s not a lot of competition in the town of 7,000.)

Little by little. That’s how the Ruckdeschels, born and bred in Middletown, ended up leaving the city and turning to the land, clearing trees with chainsaws to build a log cabin on a hill in the woods, going from thinking homeschooling was “weird” to homeschooling their five children.

“We’ve been in transition, transition, transition since we got married and lived on a tenth of an acre in Middletown,” said Chris, 35. “We had a big garden out back with grapevines. We made wine.”

What Chris is getting at is that the instinct toward self-sufficiency has been there all along, particularly for Delia, who used to dream about being transported back to the time of the pioneers. “I grew up reading Laura Ingalls Wilder and I think it was the height of life,” she laughed.

“Every time we’d pass a farm and see the animals, we were like, ‘Oh, wouldn’t that be nice,’” said Delia. They owned their house in Middletown, but the more they thought and read and learned, the more apparent it became that they wanted their kids – at that point they had Florence and Giacomo, called Jack – to “grow up like that,” said Delia.

“We would sit in town and look at this book,” said Chris. “It was kind of a fairytale version of homesteading.” He goes and gets the book in question. You can see it’s a book that could stir up a young couple’s spirits. The Self Sufficient Life and How to Live It, by John Seymour, is an oversized volume with a big red barn on the cover, and in the foreground, round hay bales dotting a golden field. “Oh it’s so easy to milk goats! We’ll build a barn. We’ll clear land,” said Chris, not exactly mocking their younger selves. “That’s nice. But it’s constant work.”

If they knew then what they now know… that sentence floats off, momentarily unfinished. Pushed, they finish the thought. They would have built a smaller house and focused on building a barn immediately (the barn remains on the to-do list). Or better yet, bought a piece of land with a house already on it. Everyone told them to add 30 percent to the estimated cost of the house for the unexpected. Being resourceful and hands-on, they ignored that piece of advice – which turned out to be true. Running the electric up the hill, for instance, the contractor ran into rock and had to go around it.

Building their log cabin was the most chaotic time of their lives. Chris, who teaches English and Latin at Minisink Valley High School, would work on the house after school until dark, then go back home to Chester, where the family was renting an apartment. Delia was pregnant with Benedict, their third, and they had just gotten a puppy. Later, when it was icy and they couldn’t get the car up to the house, they would be carrying baby Benedict down the hill in the dark thinking, “Can we keep doing this?”

“We did all the things people say are most stressful on a marriage” at once, said Chris.

Yep, they might have done a few things differently. But neither of them ever questions the decision to uproot their family and start again. The more they simplified their lives, the clearer the path became, until going back to their old life would have been a violation of their faith. As Delia put it, “We know better now. And we have to live that.”

“Somebody should not have to work 12 hours a day in a chlorine filled meat trough so I can have cheap meat,” said Delia. “When I think about some of the places where they make food, and how they treat the human workers, mostly immigrant workers… How can I do that and be okay with it?”

Sometimes it gets overwhelming. When the goats’ hooves need trimming and the kids are running amok and they’re late for a get together with another home school family.

Then they look at their five children. Now two of them are sitting at the long kitchen table, paging through that fateful book, The Self Sufficient Life.

“These are all the animals that can destroy the garden,” Beatriz, 8, tells Benedict, 6. She turns the page. “These are good bugs, because they eat the bad ones.”

“What my daughter knows compared to what I knew at that age,” said Delia, of 13-year-old Florence. “She can milk goats, takes care of rabbits, she helps me process rabbits, we have Florida Whites for meat. Florence has pretty much taught herself to make parchment from rabbit skins, she made leather from a lamb skin our friend gave her at Easter.”

I ask whether the kids ever feel like they’re missing out on chicken fingers. The family eats a much simpler diet than most of us are used to: rice and beans, homemade bread and homemade pasta, greens from the garden or co-op, potatoes, pickles, caponata, occasionally a chicken breast. They don’t eat meals out and can count the times they’ve been decadent and gotten pizza. Their exotic imports are olive oil, coffee, and olives.

Delia, who is careful not to answer for the kids, passes the question along when they come downstairs later. No, they answer in unison, like it’s the dumbest question ever.

“Florence has kind of adopted the rural, I’m a farmer mentality. I’m more concerned,” said Delia, “that she doesn’t become a snob about it.”

The following story has become family lore: Delia was at the hospital, giving birth to Beatriz, now 3, who was premature. The older kids were home with their grandmother. While Delia and Chris were gone, one of the family’s dairy goats gave birth to a stillborn kid. Florence, then 10, announced: “Nana, this goat needs to be milked.” She stood the goat up and milked her right out, having never done it before.

They think of their kids in that historic way – as assets. “And then they also see themselves as valuable for something real,” said Chris. The kids shovel the driveway by hand like a team of plow horses (and since they are homeschooled and don’t get snow days off, they are some of the only kids on earth who don’t like snow). Jack, 11, is getting interested in hunting and wood carving. Delia’s mom, who lives in Middletown and works as a seamstress, is teaching the girls to sew. They more than pull their own weight on the land and in the house. Even little Gesina, 3, gets the message. When she wants to play with the water in the sink, she asks if she can “wash the sink.”

Chris and Delia, meanwhile, grew up minutes away and a world apart, in what Chris calls Generic America. Chris played guitar and drums, sports and video games. Asked about religion, he’d say he was a Yankees fan (he now leads a kids’ choir that sings at church). In high school, he would tease Delia when she couldn’t go out on a date because she had to do house work, saying that her family was keeping her in the basement, making shirts. It still makes both of them laugh. He went to college because he was supposed to, ran cross country because he was supposed to. “I didn’t have any goals,” he said.

So when his son hankers to play video games, he gets it. Think this through, Chris will urge. “What are you producing playing a video game? You spent all this time, you could have been developing yourself or helping people.”

It’s not just saying no, don’t do that. The flip side is introducing things they like to do that are yeses, that could also turn into adult interests. For Christmas, Jack got a high quality set of carving tools for woodworking. Florence got a calligraphy set.

Although the classical curriculum they’re studying requires more discipline than a public school education, they may not go on to college. “We tell them that repeatedly that we don’t feel at all that they have to leave at 18 or 21 or any age,” said Delia. “We’re encouraging them to really think of something they want to do, they really enjoy. How can you use that to create your own purpose, to live a fulfilled life?”

From a financial perspective, college is a question mark, said Chris. The model of leaving at 18, going into debt, marrying someone else in debt, and then digging yourself out of a hole is not all that practical. Why not stay in the context of the family, and put the money that would have gone toward tuition into starting a business or niche market that would be helpful to the community? “There are so many advantages. Costs just disappear,” he said.

They are a thinking family. They have time to think, pray, meditate; they don’t have TV. Looking down the driveway, you can’t see the road. “Not a lot of things are peaceful now. You have to force the issue,” said Delia.

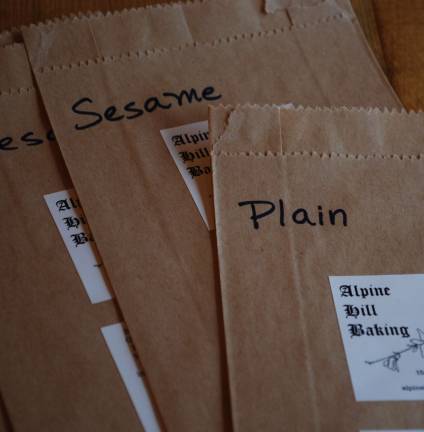

The bread has come out of the oven and is cooling in a vintage bread rack. Delia is scooping granola into brown paper bags, then weighing each bag on a scale. In ten years, they have come a long way, but they’re not yet where they want to be. They are still in transition, transition, transition. They want a barn, then they can get a cow.

They’re not too concerned about making all their own food, which was one of their fairytale aspirations. They have realized along the way that people who do that have been homesteading for decades, or grew up doing it. Sometimes Delia picks a week in which she’ll make all the family’s food – and that turns out to be the week they get in a jam and order pizza.

“People talk about sustainable in terms of the environment, but it’s got to be sustainable in terms or your life or you’re not going to do it,” said Delia. “If you can do one thing,” like keeping chickens for eggs, “well, that’s a big thing.”