Raw milk

Why are people driving hours for their fix?

Glass mason jars clank as Mary Juliano heaves one cooler after another into her minivan. She picks up two envelopes labeled eggs and milk, peeks at the checks inside – $60 for 15 dozen eggs and $92.25 for 41 jars of milk – and backs out of the driveway.

For 10 Warwick families, Mary is the milkman this week. They cant buy their milk at the grocery store, because the milk Mary is picking up is unpasteurized, and according to the FDA, dangerous.

Each state regulates raw milk as it sees fit, from banning it altogether in New Jersey to selling it retail in Pennsylvania. The most common arrangement is the one in New York, where you can only buy raw milk on the farm it came from.

Mary, mother of five, belongs to a CSA year-round and recently installed solar hot water panels. She likes raw milk because its closest to the earth. Im glad to be able to drink that and not feel like its been altered. She has it with cereal, makes it into yogurt and butter, and blends it with fruit and agave syrup to make smoothies for her kids.

Her destination, 40 minutes northwest, is Freedom Hill Farm in Otisville, with a stop at Kirby Farm in Middletown for free-range eggs. Freedom Hill Farm doesnt advertise, but since it started selling raw milk in 2007, word has spread like wildfire: Theres this woman with this farm. You can eat off the floor. Its raw milk. So-and-so says its the best milk you can drink. Freedom Hills base of regular customers has grown to 700. Some make pilgrimages from as far as Manhattan.

Mary parks and shouts a greeting to farmer Julie Vreeland, whos forking hay from the back of a golf cart into a calfs pen. The small parking lot has two other cars in it, and more pull in as Mary unpacks 41 empties and loads full bottles into the coolers. Julie and Rick Vreeland had no intention of becoming the hub of a movement. Timing is everything.

When Rick Vreeland says the milk you buy at Shoprite is just white water, well, for 26 years that was his milk. Half a life ago, Rick started one of the states biggest dairies, a 2,000 cow factory farm in Slate Hill.

The milk was homogenized to break up fat globules, pasteurized, and sold at grocery stores at the price the government set. The grain-eating cows and the humans were pushed to their production limit. Not your government man, Rick took a job with the county to make ends meet. After two and a half decades, this situation got a little stressful. The Vreelands sold out to Ricks partner and bought the old farm from Ricks dad.

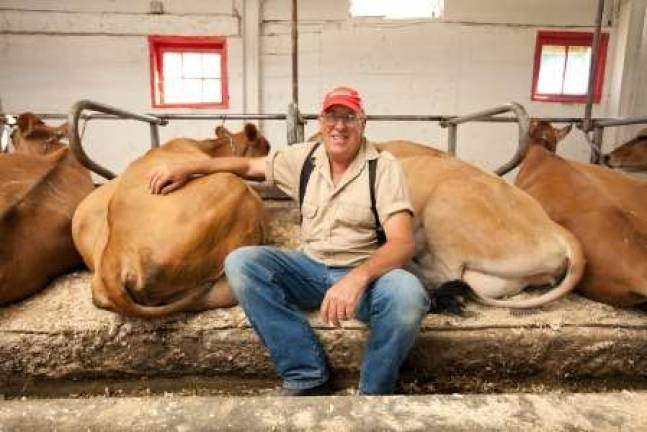

This time around, the Vreelands settled on practices somewhere between todays and those Ricks great-grandfather (who died right there, said Rick, pointing to the barn floor) might have used. The Vreelands have 54 Jersey cows, grazed in the pasture, and milk 30 of them. The John Deere tractor out front was Ricks grandmothers. I use it every day. I just love to hear it run. Visitors can see the milk travel from vacuum cups attached to the cows teats through the circa-1960s milking system, headed for a tank in a sanitized room, to be hand-bottled.

Their vision was to start a visiting and teaching farm, while creating a business to be handed down to the next generation. They went with raw milk simply because it didnt seem worth sending 186 gallons of milk a day to a processor.

While the cows are being milked, Rick, Julie, and three teenage girls who want to be vets brush the cows, moisturize a dry udder, salve a bruise. When a cow lies down on the barns memory-foam floor (perhaps the most modern of the farms equipment), the girls pile on top of the cow, which seems not to mind in the slightest. Time your visit right, and you might walk out with milk that was in the cow when you arrived.

This is the way farming should still be, said Rick. Small, you can raise a family, get intimate with the animals. Selling raw milk at $4.50 a gallon straight to the customer – plus, recently, pasteurized kefir and yogurt – the Vreelands now have a viable business. I have better cash flow here than I did with 2,000 cows, Rick said. With the respect that when I get bills, I can pay em.

Raw milk drinkers say it eases maladies from asthma to eczema to cancer. At five percent fat, its creamier than whole milk but doesnt make you fat. One of the Vreelands customers is on a raw milk diet, consuming nothing else for three months. That it can be drunk by the glassful by people who are normally lactose intolerant, this writer can attest. But of all its benefits, not the least is its potential, in an age of behemoth farms, to resuscitate the family dairy.

James Kleister, 25, jogs outside in his socks when I arrive, thinking Ive come to buy milk. A few years ago he caught wind of what was happening 25 miles to his west at Freedom Hill Farm. When I saw the farm in Otisville, I saw yeah, it can be done. He followed suit.

The fate of the 200-year-old family dairy in Washingtonville, or the 50 acres left of it, lies entirely on his shoulders. Until recently, things didnt look good. It costs $1.50 to produce a gallon and youre getting $1 per gallon, he said. It doesnt cut it.

Aimee Polman, 23, lives a mile down the road from Kleisters farm. She learned about raw milk when she researched it for a communications class at Orange County Community College. But Freedom Hill, then the closest source, was too far. Raw milk remained a hypothetical until she saw Kleisters sign.

Now she buys a $5 gallon a week for herself and her mom (thats $4 more than Kleister was getting per gallon three years ago). Four aunts, and a couple family friends have started getting it, too. Polman likes the milks fresher taste. Shes into the idea that it hasnt been processed. Best of all, she hasnt gotten a cold, sore throat, or sinus infection since she started drinking the stuff.

Kleisters Udderly Fresh Farms has 100 customers like Polman, but persuading the mainstream is not proving easy. With the privilege to sell unpasteurized milk straight to the public come regulations exponentially more strict than those at a conventional dairy. Still, a lot of people stop by, they want to buy milk. They hear its not pasteurized and they wont try it, wont even look at it.

Not until he builds his base to 300 customers will Kleister feel confident that his dairy and its herd of 35 cows will continue into a fifth generation.

Before she started milking them, Lisa Ross kept goats as pets. Shed dress them up in pink sweaters and university hoodies. She raised one that had been abandoned by its mother in her house, until it started humping everything and eating pictures off the wall. I dont have kids, she said, so I think I have a lot of animals to substitute.

When she and her husband John, who run a dog boarding business from their Goshen property, needed an agricultural exemption to lower their taxes, they tried boarding horses. That didnt work out. Lisa started breeding and milking her goats. Unsure whether she had enough milk to go into the bulk tank for pasteurization, she got her raw milk certification and started selling her milk for $25 a gallon.

And the people started coming. Like the Saudi royal staying at the Ritz-Carlton in New York last winter whose six henchmen would pull up to Ross Farms weekly in a black S.U.V., paying in hundreds.

The Ross goats moonlight as b-list celebs. Ginger was on the Letterman Show, dressed up like a peacock spoofing the birds escape from the Bronx Zoo. The rats backstage at Lettermans studio are so big you could milk em, laughed Lisa. A $750 check from the Dr. Oz show is displayed in on the milk room fridge, along with a permit to bring the goats to the city.

Ross Farms is experiencing more demand than its herd of 50 – 15 of them milking – can supply. I tell everybody to call. Please, please call, said Lisa, as she cleans Moomoos teat with iodine, preparing to milk her. They dont like that, when they show up and theres no milk. I usually dont have enough milk for everyone who wants it. I have to save it for people who really need it, people who are sick or have babies.

She stopped selling to the public this year from August to January, but she makes exceptions. Frank Golio, 33, of Monroe, gets this VIP treatment. A year and a half ago, he and his partner didnt know what to do about their three-month-old son, who had developed colic on formula. A gay couple, they didnt have access to breast milk. They went to their holistic pediatrician. The closest thing to breast milk? Raw goats milk.

Raised on the Ross goats milk, the 19-month old twins now have insanely aggressive immune systems. Golio has been using it sparingly in anticipation of the winter shortage that happened last year, even buying extra and freezing it.

But if he should run out while Lisa is resting her goats, the babies wont have to be weaned cold turkey. She may milk here and there, said Golio. Lisas really good to me.

The pasteurization debate The milk you buy at the grocery store has been heated to 161 degrees for 15 seconds; if its been ultra-pasteurized to extend shelf life then its been heated to 280 degrees. Weve been pasteurizing milk since the Industrial Revolution to kill disease-causing bacteria like salmonella and e-coli.

FDA: Raw milk is dangerous. It can harbor dangerous microorganisms that cause diseases like listeriosis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and brucellosis. Dont drink it, period. Pasteurization does not affect milks nutritional value or cause lactose intolerance.

Raw milk proponents: The high heat used in pasteurization is an equal opportunity killer that cooks out vitamins, fatty acids, antibodies and enzymes, including the lactaid that helps digest milk. The milk produced by healthy, pasture-grazed animals in a clean environment by conscientious farmers doesnt harbor dangerous bacteria and doesnt need to be pasteurized.