Following the paper trail

By Becca Tucker

“We do things that aren’t really considered possible,” says Steve Smith, his voice coming into my headset through a mic attached to his own. “We take old newspapers and up-cycle them into label papers and printing papers.”

Smith, a tall man full of Midwestern affability, oversees operations at the paper mill that manufactured the pages in your hands right now. We’re proud of Dirt’s 93% recycled paper. It makes us feel virtuous, looks good on our masthead and sounds good in the press kits we give to advertisers. So when a saleswoman from a printing company, competing for our business, told us the recycling process was so energy- and chemical-intensive that recycled paper wasn’t any greener than virgin paper, we decided she was full of it. But the more we thought about it, the harder it was to ignore the fact that we knew bubkis about how Dirt was made.

So we booked a multi-city flight to Chicago and Detroit – respective neighborhoods of our paper mill and printing press – to see our own story spun.

1. Our forest is your recycle bin

Our pilgrimage begins 13 miles from downtown Chicago, at FutureMark Paper in Alsip, Illinois. If you’ve ever driven past a pulping operation, you understand why Medieval law required paper mills to be erected a certain distance from city walls. But here, it just smells slightly… toasted.

Smith apologizes before we approach a mountain of paper bales. He has no control of the content of the bales. And “dirty magazines,” he shrugs, “tend to use better quality paper.”

I don’t see porno, but I do see plenty of other kinds of dirt that could jam up the equipment: plastic cups and bags, a cracked CD, staples. Recycling’s rule of thumb is white paper in, white paper out. To make recycled magazine paper, which is whiter than newsprint, you usually have to start with white waste paper. This hodgepodge is a far cry from white.

A backhoe shovels crumpled newspapers, magazines, and the occasional Miller Lite six-pack holder onto a conveyor belt, a monitor displaying the varying brightness of the paper as it passes. The plant is down for the day for maintenance, at least most of it. But even with its guts shut off, the paper mill’s ravenous mouth – which eats up discards from printing plants and recycling from the curbsides of Chicago and Daytona – hasn’t stopped to take a breath.

Once, in these recycled paper bales that FutureMark pays good money for, they found an engine block; another time, a car seat.

“There’s been a real downgrade in our quality since recycling went single stream,” said Smith. “We’re one of the few that can actually use this crap and still make paper out of it.”

2. Out, damned spot!

Recycling’s life stages dictate that paper get darker and stiffer the more it’s reincarnated. Not here. A $120 million de-inking facility, installed a decade ago, sends the paper through a12-hour, 14-step washing process that will free the fiber from staples, plastic, coating, binder glue and ink.

The de-inking process begins with a pulper, which looks like a large horizontal front-loader washing machine that rotates, paddles, and tumbles the fiber. Cyclonic cleaners spin heavier glass or plastic bits to the outside; filters screen out anything over twice the width of a human hair; and oily soap bubbles pumped up through the fiber carry ink to the frothy top. Imagine a just-poured glass of Guinness.

“Most recycling plants use like a huge blender” to separate paper fiber from contaminants, Smith explains. Everything gets chopped up into tiny pieces, “then they spend the rest of their life trying to get those pieces out. If you can get it out as a milk jug instead of a million tiny pieces of plastic, you’re way ahead of the game.”

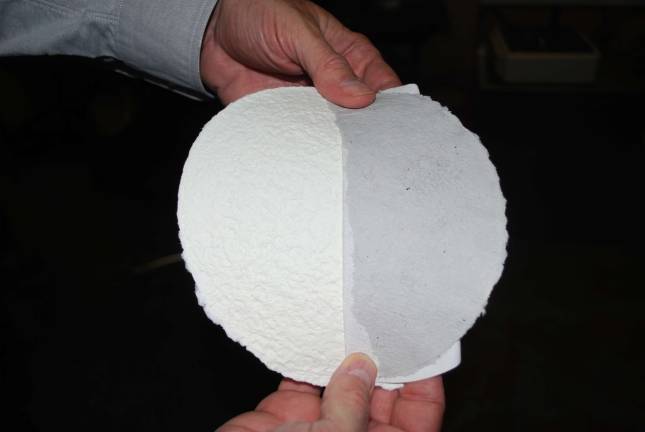

Instead of bleach, peroxide – which breaks down – is added to reverse the yellowing that makes old newspapers look old. Some other proprietary de-inking chemical is added as well, gentle enough that the fiber remains strong, allowing FutureMark to make a groundbreaking 100% recycled sheet. (Usually some virgin fiber must be added, because the recycled fiber on its own is too weak to hold up to the papermaking and printing processes). Even the ink and coating that’s collected in the cleaning process is reused, becoming a product similar to limestone that local farmers use to improve their soil. Ashes to ashes, Dirt to dirt.

3. The one percent

The washing process churns out a uniform white pulp that won’t jam up the machines or make slime spots or holes in the paper, the kinds of things recycled paper used to be notorious for.

After that, “we make paper about like everyone else,” says Smith.

Which is to say, fast. The liquid pulp is collected in the headbox, which sprays the slurry across a conveyor belt. Moving at up to 30 miles an hour, the pulp flies through 32 dryers that squeeze, steam and bake out the water. (The heat is recaptured to heat the building in the winter). Once dry, the sheet passes through a coater, which slaps on a glossy or matte finish, and then over a heated roll that seals the coating and irons it out. Periodically throughout this process, a monitor checks brightness, color, gloss, weight, moisture, and thickness.

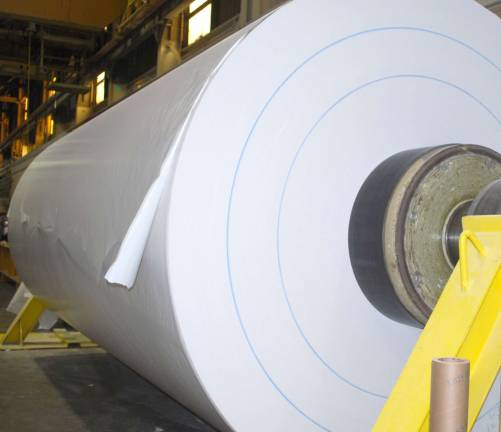

What look like oversized pizza cutters slice the massive 40-ton spool into one-ton rolls that will be shipped to printers. In a satisfying loop, the American Airlines in-flight magazine – which tends to remain in the seatback pocket – is printed at FutureMark and then returned to FutureMark, to be recycled into new paper.

The 500 tons of recycled paper made here every day account for one percent of this country’s total paper supply. You’ve seen it on Campbell’s soup cans labels, the pages of Outside magazine, and of course Dirt.

4. Ink meets paper

Next stop is Midland, Michigan, where Quad Graphics, the largest magazine printer in the U.S., prints the little guys: medical journals, newsletters, regional magazines like yours truly. They’re all set up for visitors, with a snack pack and DVDs in the waiting room. When times were flush, editors from glossy magazines would fly in to oversee the printing process, make sure the colors looked good on important ads. That doesn’t happen much anymore.

They keep me entertained, showing me an extensive recycling program that separates everything from the wood core plugs that come in the ends of paper rolls, to the paper dust that’s ground off the edges of magazines before they get their bindings.

Finally Dirt’s cover is next up. Press technicians pop nickel and aluminum plates – laser-etched with the words and images we’ve sent digitally from Dirt headquarters – into each of four printing towers. There’s one tower for black, one for cyan, one for magenta and one for yellow.

The one-ton paper roll accelerates until it’s unspooling through the press at five miles an hour. Only then does the image start to form: first just in yellow so it looks like it’s at the tail end of a century’s fade. It’s the black-and-white cover of the Appalachian Trail hiker; who knew it would have yellow in it? Then the darker colors kick in, the press gears up to seven miles an hour, and the image starts to pop.

Déjà vu. I’ve watched this photograph, taken with a wooden Civil War-era camera, develop on a glass plate in a pool of chemicals. Now I see the hiker’s thousand-yard gaze and Salvation Army gym shorts re-emerge. This time there are 22,000 of him.

5. The long drive home

The cover and the inside pages, which are printed on different press, get married on a mechanical stitcher that staples the pages together. Pumping knives slice the pages so they’re even, and a strapper slaps plastic straps onto bundles of 25 magazines.

The bundles are packed onto pallets and onto a truck, headed to a distribution center 700 miles away in Newark, New Jersey. From there, multiple trucks deliver the magazines to local post offices, where mailmen stick them in sacks and bring them to your mailbox.

The pages you’re reading now might have a little bit of Chicago Tribune in them, a graded homework assignment, a cardboard box, a love letter. They also contain six percent virgin pulp, which is, at this stage in the evolution of American recycled paper, necessary to give the sheets enough strength to make the journey you just read about. Their manufacture requires less water and fewer chemicals than virgin pages, and using this paper keeps 18 mature trees in the ground per issue. The magazine does have to travel a third of the way across the country to get to us, but if we want recycled paper, we don’t have much choice in that matter. The fact that when an American magazine like Fast Company decides to print on 100% recycled stock, it gets its paper from Germany – that tells us something.

So the verdict, after spending $1,000 on flights, motels, trains, cabs, rental cars and Tim Hortons? We’ll continue feeling bigheaded about our paper.

Made (harder) in the USA

Good as we are at making trash, turning that trash back into paper is not our best thing in this country.

But why? It takes less energy to make recycled paper, and prior to 1850, paper in America was made from anything but trees: blue jeans, plants, hemp.

During the westward expansion and logging of the 1850s, our paper industry was built around virgin trees, and now, including recycled paper in the mix slows down the cogs. The government has spent billions financing the virgin fiber industry and building roads into forests for lumber extraction, but doesn’t subsidize recycled paper. We send most of our wastepaper to China, where it might be turned into packaging which, after traveling 10,000 miles round trip, comes back to you encasing your new iPhone – a balletic exchange that has driven the cost of recovered paper up fourfold since 2000. We’ve gone from multi- to single-stream recycling, which contaminates the stock that feeds recycled paper plants.

Pile these setbacks on top of the current state of the print industry, and it’s not hard to see why FutureMark is one of only three paper mills in North America specifically designed to take in recovered paper and pump out high quality white paper.