Fix my brain please

ADHD has become today’s scarlet letter among students, synonymous with troublemaker. Once you’ve been labeled, little can be done to redeem yourself besides start fresh at a new school – and even then, school records may transfer over and taint the fresh environment with a lowering of expectations. Regardless of intelligence, talent or capability, kids with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder often assume the role that has been preordained by the competitive environment of the classroom: that of the dunce or class clown.

It’s easy to understand why prescriptions for methylphenidates (Ritalin) and amphetamines (Adderall) continue to soar, why there was a twentyfold increase in the consumption of drugs for attention-deficit disorder in the 30 years since 2012, according to psychologist L. Alan Sroufe in Ritalin Gone Wrong. Pharmaceuticals are the-tried-and-true workhorses for getting the job done.

Yes, alternatives exist, but our society’s need to see results – and fast – especially as our children’s grades slide and their confidence diminishes, often leads us to seek the quick fix: pop a pill, see a change.

The medical community first coined the term “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood” in 1968 to describe the sort of restlessness, distractibility, over-activity, and short attention that has now turned into a national epidemic. Since then, the name of the disorder, along with its definition, have undergone multiple permutations. As our body of knowledge grows, so do concerns about its go-to treatment.

There are always potential side effects, with any drug. With stimulants like Ritalin, Adderall, and Dexedrine, these include loss of appetite and stomachaches, anorexia, irritability, sleep problems, rapid pulse and higher blood pressure; very rare complications include heart arrhythmia and possible lowering of the seizure threshold.

“It’s very common that parents would say [their children] just don’t eat until dinner... They just don’t eat,” said Dr. Miriam Grossman, a Suffern-based medical doctor specializing in child, adolescent, and adult psychiatry. As a result, children taking these medications may have trouble gaining weight or lose weight.

There’s also emerging reason to worry about medicating kids for a condition they don’t even have. Studies are revealing “healthy” control groups in addition to people with ADHD see effects from taking Ritalin: increases of dopamine in the brain and improvements in attention and concentration. Often, these Ritalin-induced performance improvements are taken as corroboration that a child indeed has ADHD in a troubling tautology. Kid does better on Ritalin, so kid has ADHD.

“Pseudo-ADHD” children may actually have an anxiety disorder or challenges at home that have led to behavioral problems. They may suffer from an “environmentally-induced syndrome caused by too much time spent on electronic connections and not enough time spent on human connections, i.e., family dinner, bedtime stories, walks in the park, playing outdoors with friends or relatives, time with pets, buddies, extended family, and other forms of non-electronic connection,” wrote Dr. Edward Hallowell, child and adult psychiatrist who has written extensively on this topic. Ritalin can aggravate an already tenuous situation. “The last thing a child with ‘pseudo-ADHD’ needs is Ritalin,” wrote Hallowell.

Even health care providers quick to acknowledge the reality of ADHD are beginning to express concerns over treating such a huge population of young children with stimulants if many of these ADHD diagnoses may be false positives.

Dr. Grossman, the psychiatrist from Suffern, is a strong believer in the power of medicine. She used to write prescriptions day and night, very often for ADHD, and was initially skeptical of the notion that there may be alternatives out there of comparable or even superior efficacy. “I’m not an alternative medicine person,” she said.

Yet when an acquaintance, an accomplished businesswoman who had built a corporation worth millions working from home, confided in her: “I’ve gotten more out of six months of neurofeedback than I did from 20 years of intensive psychotherapy and medication,” Grossman began to delve into this brave new world called neurofeedback therapy.

She became intrigued by the possibility of treating people with something benign “that can actually address the core of the problem,” rather than just altering brain chemistry temporarily.

“Neurofeedback is much more holistic than psychiatry,” she said. “In psychiatry there’s a cookbook approach: we look at symptoms and determine if they fit certain criteria, at which point we make a diagnosis.” Neurofeedback looks at the brain as functioning primarily on an electrical system, with chemical functioning secondary to the electrical. “If we can affect the electrical, then we can change the total regulation of the brain.”

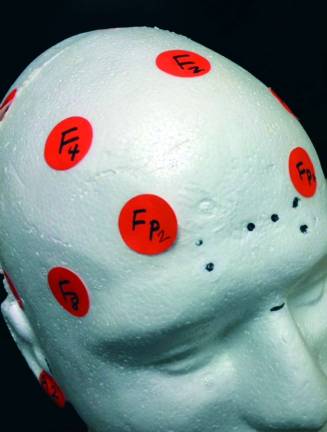

Grossman compares neurofeedback therapy with walking past a mirror, observing that one’s posture is slumped, and then automatically and without thinking making an adjustment. An electroencephalogram, or EEG, affords the brain the opportunity to view itself in this kind of mirror. It wants to be healthy, so when you give the brain information about itself, it uses it to self-regulate. Sound hard? This all happens as you sit there and watch a movie. The only restriction? It has to be a movie you want to see.

On a weekday afternoon, a middle aged woman settles into a leather chair to watch Something’s Gotta Give, a romantic comedy in which Jack Nicholson dates much-younger women until he falls for his girlfriend’s mom, Diane Keaton. “Have you seen this one?” asks the technician in scrubs, who’s placing electrodes on the woman’s head. The woman shakes her head as she puts on her glasses.

After the opening credits, the movie gets choppy, like the DVD has been scratched. That’s because the woman’s brain waves have taken over the running of the movie. When her brainwaves, which can be seen undulating on a computer screen like colorful jellyfish, are off-target, the movie pauses for a split second. Greedy for more movie, her brain self-corrects.

A 15-year-old boy with a crew cut comes in with his mother, tosses his coat on the floor and plops himself down in the other chair. He opens a DVD case he brought from home — The Labyrinth, that weird 80s classic starring David Bowie. It seems a fitting choice. Is there any more elaborate and inscrutable, and sometimes inescapable maze than one’s own brain? That three-pound mass that uses 30 percent of the body’s energy supply?

His mother watches anxiously from the back of the room. Her son, she explains later in the waiting room of Warwick Brain and Spine Therapy, has Aspberger’s and ADHD, and the “things that go with it, like intermittent explosiveness.” She asked that we not use his name.

He has been on 40 or so medications “that don’t work,” she said. “Medications don’t work for Aspberger’s, and sometimes they have adverse effects,” she said.

In the copious reading she’s done about her son’s condition, just in the past three years or so, neurofeedback has started popping up. But it was her son who asked to try it, after he saw a presentation about neurofeedback. This was just his second session.

“You know what?” said the mother. “You’re not supposed to see a difference” this fast, “but I can tell you he’s trying harder.” Whether it was because the treatment was having an effect, or because her son wanted it to work, he had managed to settle down after a little argument that would usually have set him off, she said.

People seek neurofeedback for conditions ranging from PTSD and anxiety and insomnia to autism and Tourette syndrome to the fog of so-called “chemo-brain.” High profile executives use it to improve performance. The military uses it at six bases. For alcoholics, neurofeedback can change the taste of booze (but you should keep going to Alcoholics Anonymous, too.)

Dr. Calvin Hargis, the chiropractor and neurofeedback therapist who runs the Warwick practice, hooks himself up once in awhile. “It’s very calming for me,” he said. “I find it increases my focus tremendously.”

Depending on the idiosyncracies of each person’s brain, electrodes placed on the head cater to dampening particular brain wave abnormalities and strengthening desired frequencies. For those with ADHD, the focus may be to “downtrain” excess alpha waves in the frontal lobe. In restoring brain balance and brain function, Hargis explained, you don’t just fix abnormalities — it tends to normalize everything, like low self-esteem, anxiety, insomnia.

“Over time, the brain actually re-wires itself, makes new neural connections,” said Hargis. It even builds brain mass.

It sounds like hooey. Detractors warn that there’s not much hard evidence proving neurofeedback, which can be fairly expensive, is all it’s cracked up to be. A 40-session course, the standard for ADHD treatment, costs about $3,500 at Warwick Brain and Spine Therapy, Hargis’ practice.

But the American Academy of Pediatrics recognized neurofeedback in 2012 as a Level 1 Best Support treatment for ADHD, right alongside conventional medication. A 2014 in-school Boston study published in Pediatrics demonstrated that children receiving neurofeedback treatment made faster and greater improvements in ADHD symptoms than the control on traditional meds, and maintained these improvements at the six-month follow-up. A standard stimulant’s effects wear off in approximately four to six hours.

Hargis emphasizes the importance of pairing neurofeedback therapy not only with cognitive therapy, but also exercise, so children can burn off excess energy. That is a point not to be overlooked: kids need to move, some a whole lot more than others. Sustaining focus in the modern-day classroom, with its focus on thought-based activities, can be nearly impossible for those who are hardwired for action.

“This concept of having kids sit in neat little rows with their hands crossed on top of their desks, waiting to listen to what the teacher tells them to do” is problematic for ADHD students, said Michael LeRose, a high school teacher, musician and owner of The Warwick School of Music and Performing Arts. They “learn better when they’re able to stimulate themselves by moving around the classroom, doing activities, tactile stuff.”

“I’ve worked with many kids with ADHD, and I’ve found that most of them are brilliant,” said LeRose. “When they’re actually involved in playing the music, I don’t see any symptoms of ADHD, since they’re actually processing, they’re moving, they’re using physical exertion.”

Psychoactive drugs, meanwhile, are not only toxic, but largely ineffective, in Hargis’ view. They “may increase focus temporarily, but that doesn’t mean kids are focused on their schoolwork,” said Hargis. They could be focused on something completely unrelated— the red, shiny shoe of the girl next to them, for example.

“I’ve always been a searcher,” said Hargis. “Chiropractors are holistic,” he said. They believe in natural cures that allow the body to do the work of healing itself. “Neurofeedback is an alternative therapy that accomplishes just that.”