Wresting a school courtyard back from the weeds

With many hands and a little Pemba magic, a principal’s vision comes to life

Principal Ferzeen Shamsi of Claremont Elementary School in Ossining, NY, invites me into her sunny office. Admittedly, the prospect of “principal’s office” still sparks a wee bit of childhood dread, even in the middle of summer when the school is abuzz not with backpack-laden preteens but administrators and groundskeepers preparing for a new school year. “Aysha, come, come,” she says.

I’ve known Shamsi, another Rockland County native, for as long as I can remember. She’s the older sister I never had. “It’s a mess,” she says of her office, crowded with the makings of classroom assignments, each student’s profile thoughtfully matched with a teacher and other students.

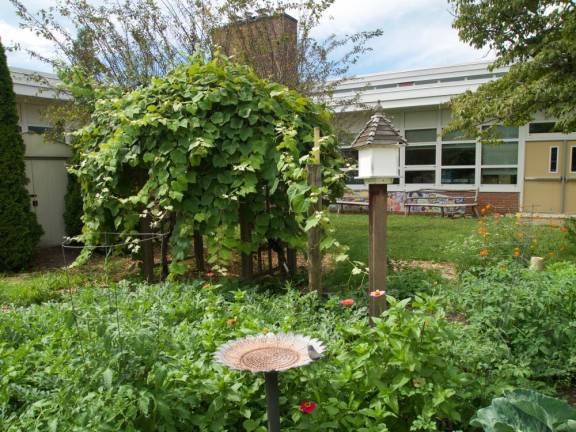

“It’s a workspace, and it’s beautiful!” I remark, referring not just to her office, but to the garden oasis just outside her window. We walk through the double doors into a central courtyard, and it seems we have stepped into another world entirely. A flowering cherry tree provides a welcome patch of shade near a few well-placed reading benches, a grapevine-draped arbor heralds the passage into a series of bountiful planting beds — herbs, tomatoes, melons, zucchini, lettuce. A (now-endangered) monarch butterfly lands on a zinnia in full bloom.

I first visited the garden in 2016, soon after it was established with the help of a farmer-naturalist from the Food Bank of Westchester and a $5,000 community grant from Lowe’s for tools, supplies and soil. Back then, the arbor had just been built by one of the groundskeepers. And there was a wigwam near the cherry tree. At the time, Shamsi, then the assistant principal, had wanted an engaging way to teach fourth graders about Native American life during the Colonial era — the way they lived, how they survived, what they ate.

Many gardeners will have heard of the principle of “the three sisters,” a companion planting technique coined by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), credited with sustaining the Colonists through their first years in the New World. What you may not know is that many tribes used the stacking method, sometimes incorporating a fourth sister. “[We] researched this and realized that it was corn, beans, and squash, with the sunflower being the last sister,” said Shamsi. Who knew?

The Colonial garden concept quickly evolved as Shamsi watched the kids in the space. “With children, especially young children like eight and nine years old, there has to be an immediate gratification in the garden when they come in, and so then it evolved to, ‘Well, let’s grow some herbs because they can immediately smell, touch, taste, right away,” she recalled.

For one student in particular, M., the garden proved transformative. “The year that he came here, he had some behavior issues that didn’t allow him to stay in class for more than two minutes,” said Shamsi. “He had some learning troubles and a lot of energy in his body, and so every single day he was being removed from the classroom for disrupting and it was defeating for him.”

One day, M. spotted Shamsi in the garden, getting ready to work the soil. He walked right up to her and said, “I want to do this. You teach me, I could do it.” Here was an opportunity.

“And so in order for him to earn his time in the garden, he had to sustain a few minutes every day doing some work in the classroom. And he did. He was able to work for the privilege of coming into the garden, and he took ownership of this space,” said Shamsi. M. went on to become the steward of the garden that year, showing the children around. “He was so proud,” she said, “and he found success in this space.”

“When I first started the garden eight years ago,” said Shamsi, “it really was because I liked gardening and I thought this space [could work because] there’s no predators.” Any gardener contending with the typical garden pests and spending inordinate amounts of time and energy on fencing and physical deterrents will understand the astuteness of Shamsi’s observation. A completely enclosed space with great sun encircled by noisy children — gardening genius, a trait that runs in Shamsi’s family.

She fondly recalls her grandmother, Ma, and her green thumb. “When I was little in Zambia and Ma had these roses and her favorite flowers, carnations,” she said. “She would grow the biggest, biggest carnations. My mother would tell me stories of when they were little in Pemba, a little town in between Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, and Livingston, where Victoria Falls is... and so people had to pass through this little town. My grandfather owned the only gas station and general store and [people would] stop for gas and come in and chat and Ma had this beautiful garden with fruit trees and flowers everywhere. It almost felt like this oasis in the middle of this, like, jungle area.”

Shamsi picks a grape off the heavy cluster hanging from the arbor. “Try one,” she says. A bit tart at this time of year, but juicy. “Now last year, we didn’t have the garden here, but the vines were just so fruitful. We had tons of grapes,” she said. “They were very sweet and nobody was touching the garden.”

While sweet grapes were a pandemic plus, the rest of the garden fell into general disrepair during the lockdown. “I can’t even tell you how many weeds just grew,” recalled Shamsi. “It was very disappointing and I tried very hard,” she said. “Lots of people came and visited hoping to support me in taking on this project,” she said, “but for some reason [there] wasn’t a commitment.”

Then, earlier this year, a community organization founded by two Ossining alums stepped in. ENU Builds – for “Empower, Network, Uplift” – sent member Leah Nelson to look at the garden. Yes, she could help with volunteers and donated plants. “She really supported the vision, and I have to say, looking around this garden, she has done everything that I have asked for and then some,” she said. “And so this year I was able to achieve it.”

That vision is twofold. One: children actively engaging in this space, being empowered to take control of their diet, all the while learning about physical and mental health and sustainability. Or even getting lost in a novel – for the bookworms, it’s a reading garden, where they can plop down with a book and forget the world for awhile.

Two: the produce going to the growing number of families that could use it. “Over the years the population here in our district has really changed,” said Shamsi. “We’re now, I would say about 60 to 65 percent free- and reduced-lunch.” Beyond sustaining the minds, bodies and spirits of the 700 children at Claremont, the bounty feeds the wider community through donations to the Food Bank of Westchester. Claremont has also partnered with a local church in Ossining, where the padre now hands out fresh produce to his parishioners on Fridays.

Shamsi is not done yet. “I would love for it to extend beyond the school,” she said. She envisions family community gardening, early- and after-school programs, even a hydroponic set-up. All it takes is persistence and a bit of garden magic.