Breaking it all the way down

Utter demolition is the only surefire ‘secure disposal’ these days

It’s the 1980s and on the curved glass screen of an analog TV, a paused image jitters behind some static. It’s the title sequence from Back to the Future. Melanie Haga, having recently lost her job in computer sales when her company folded, is sitting on her couch quickly sketching it out on some paper.

“This was the name,” she recalls thinking, as she sketched. She’d been feverishly reaching out to old contacts to build up her new business, one based on the recycling of office electronics. “I saw the name on the film pop up and immediately drew it out,” she said. “It made sense to me because I was taking things from the end of their lifespan and bringing them into the future.” She was trying to, at any rate, having set up a modest shop in her own home, originally focused on reselling used computer parts.

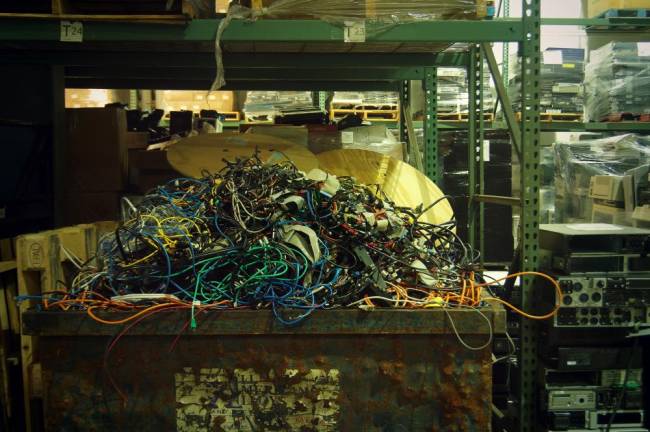

“It was very lucrative for a while, but eventually manufacturers began including lifetime services and things changed,” she said. “In this business you need to be able to turn on a dime.” And that’s what she proceeded to do. Rather than focusing on reselling parts, Back Thru the Future established itself in a new frontier: collecting electronics from offices, banks, hospitals and anywhere else with sensitive data, and breaking it all down into its component parts. “Break down” is being used in the most literal sense here. The job is not simply unscrewing hard drives and boards, but the utter demolition of everything that passes through the warehouse doors into its component parts. In come old computers, screens, printers, phones, cables and other electronics; out go pieces of aluminum or stainless steel, sent off to the smelter to be further refined and melted down.

Today, Back Thru the Future is headquartered in a 20,000-square-foot warehouse in Franklin, NJ. It has a fleet of three mobile shredding trucks, so clients can see their devices destroyed with their own eyes. The trucks are emblazoned with great white sharks and the tagline, “We Eat Hard Drives.” The biggest is capable of crushing over 2,000 hard drives an hour.

The company has grown in lockstep with its feedstock. E-waste has snowballed in the past three decades into a mess of unprecedented proportions. Today only around 20 percent of e-waste is recycled. The rest, though it’s only two percent by volume of everything we throw away, accounts for the lion’s share – roughly 70 percent – of the toxic waste generated in the United States. And that’s only part of the debacle. The other is cyber security. Data breaches are an increasingly pervasive threat, as our devices continually evolve to get smarter, cheaper, smaller and more powerful. “Even your bathroom scale probably knows things about you that other people don’t,” Haga wrote in a recent article for a medical tech outlet.

Haga stood up and disappeared from the conference room table, returning a moment later with a massive bar of metal some three feet in length. It clunked down on a side table. This bar was once hard drives. This is what “secure disposal” looks like these days. No longer is there any danger of someone hacking the data – medical or financial records, Social Security numbers, passwords, trade secrets, credit card numbers, you name it – that can hide deep inside devices. Only now is the material ready to go back out into the world to become something new, perhaps even a component in a new computer.