Food sovereignty starts here

A cross-cultural movement of seed keepers and swappers reconnects to our ‘original sustainers’

“Seeds never forget,” said Rowen White, seed keeper, farmer and Native American storyteller. White hails from the Mohawk Community of the Ahwesahsne people, whose reservation straddles the current day New York-Canada border. The keynote speaker at the virtual winter conference of the Northeast Organic Farming Association – New Jersey, White has emerged as one of the nation’s leading voices in the growing movement to repair humanity’s intimate relationship with seeds.

Speaking to the conference, White told her audience of how the Italians came to America with tomato seeds sewn into their pockets, only to find out that tomatoes – practically the Italian mascot – are not indigenous to Italy. Seeds, it turns out, can be teachers, if we stop to listen.

We’ve lost touch with our food, but seeds can lead us back home, says White, who lives with her family on the seed sanctuary farm, Sierra Seeds, she founded in Northern California. It is not too late to find our way out of this disconnected, industrialized foodscape that’s poisoning us, back to a nourishing relationship with our “original sustainers.”

Her mission is “rematriating” seeds – and humans, too – back to the land with which they co-evolved since time immemorial. She hopes to empower her children’s generation, no matter their ancestry, to love seeds as relatives, the way our grandparents did. Rematriation is a fitting word on many levels, because saving seeds is a traditional role of women in many indigenous cultures.

The urgency of her mission is clear, as seed companies large and small have run short for the second spring in a row, in the face of skyrocketing demand from newby gardeners. After the past year’s supply chain snafus, people all over are concerned about potential food shortages – and now they can’t find seeds to grow their own. Meanwhile, our country is facing crippling levels of obesity, particularly in communities of color and rural areas that have been all but cut off from access to fresh food. Corn, corn, everywhere, but not an ear to eat.

Collecting seed was once as ordinary as harvesting ripe fruit, but we’ve gotten out of the habit. Seeds are reasonably cheap, after all, and in a normal year, easy and kind of fun to buy. As we’ve left off preserving seed from one season to the next, handing our favorites down from generation to generation, what we have inadvertently done is put our food heritage and future in the hands of a few multinational corporations.

Into that void has stepped agrichemical conglomerates like Bayer (formerly Monsanto), which controls 80 percent of the corn and 90 percent of the soybeans grown in this country. Cementing their power, they design their seeds to terminate — or fail to germinate — after one harvest, forcing farmers to buy new seeds each season, along with Roundup, the carcinogenic herbicide that they have to spray on their fields of Roundup Ready crops to get a decent harvest.

“We’re out of time right now,” White said in an interview over the summer with environmental nonprofit For the Wild. “This collective amnesia, collective forgetting of agreements, has reared itself into a system of nourishment that is fundamentally broken. Is fundamentally doing quite the opposite of nourishment: It’s actually poisoning the people, it’s poisoning the land.”

Even now, the seeds we plant across our heartland reflect who we’ve become: “brokenhearted people planting brokenhearted seeds,” says White. As combines rake the prairies, harvesting monocultures of hybridized, genetically modified, privately owned versions of “beautiful corn mothers,” so we have turned into human beings with no real, inborn sense of who we are, yearning for a culture of belonging.

“We need people with a blood memory of agriculture,” she said to NOFA – NJ, noting technology is not the only thing that will save our future. “We need a diverse culture of agriculture.”

Small and simple though the act may be, seed keeping is in fact a revolutionary venture. There’s nothing particularly complex or at all high tech about the process of seed saving. Humans have been saving seed for 12,000 years, without any special training or equipment, and frugal gardeners have never stopped letting a couple plants go to seed and stowing them in the basement ‘til next spring. Still, its objective is nothing less than retaking control of our food from mega-corporations.

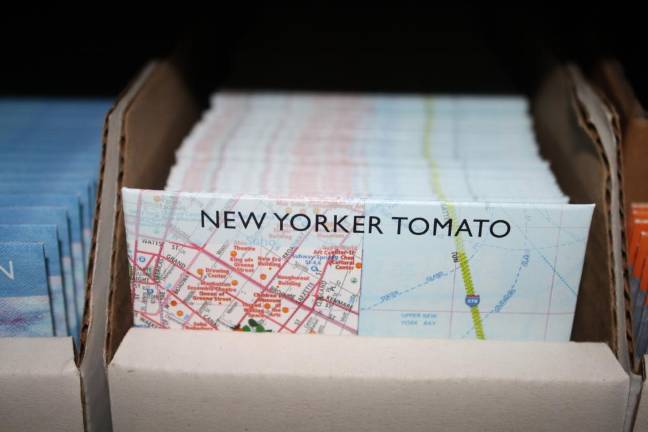

In this neck of the woods, we have a well-established champion of regional seed sovereignty in the Hudson Valley Seed Company. Librarian Ken Greene founded the company in 2009, after seeing potential, not to mention great stories, in the seed check-out program at the Gardiner Library where he worked. On their organic farm in Accord, NY, he and his crew have been tracking down, testing and propagating heirloom seeds that do well here, then sending them out into the world in iconic art packs designed by local artists.

Greene and White’s parallel seed paths intersected when they combined forces in 2017, establishing a Native American seed sanctuary in upstate New York – White’s ancestral grounds – where they planted endangered tribal seeds like Mohawk red bread corn. Over two days, Akwesasne tribal members led traditional ceremonies and oversaw the sowing of nearly extinct varieties of corn, beans, and squash – the traditional three sisters. From six pounds of corn came 800, and all the seeds and food went back to the tribe. Kids on the reservation made and sold squash pies, then sent the proceeds to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe protesting the oil pipeline.

Now, seed keeping appears to be returning from a generational hiatus to hit the mainstream once again. Without fanfare, seeds are retaking their place in our daily lives, being passed along in handmade envelopes and Ziploc baggies from friend to friend, co-worker to co-worker. The Albert Wisner Public Library will be accepting seed donations this spring to begin its own seed library, like the one that launched Ken Greene into his second career. The seeds will be available to library patrons for free check-out by the fall. The idea came from a patron who saw the program in another library, and together with library adult services manager Laurie Angle, put it together during quarantine.

Warwick gardener and artist Nicole Hixon decided to put together a seed swap this spring, after she got a kick out of participating in about six last year. When her seeds arrived, she said, “it was like Christmas.”

She ordered her own heirloom seeds from Baker Creek in Missouri, and closer to home from Hudson Valley Seed Company. “I have a seed problem,” she admits. “I try not to buy but I have a lot stashed away.” She printed up fliers for the Warwick Valley Seed Swap and posted it on Instagram. Five participants ended up taking part, two, weirdly, from California, Hixon laughed. They were supposed to pay a $10 handling fee and send in 25 packets, containing a few of these and a few of those: five fuzzy tomato seeds, say, or 30 tiny carrot seeds. Some sent in just one kind of seed, so Hixon will have to make up packets herself before sending them back out, but that’s no problem.

“Everybody gets cool stuff,” she said. “I once got moon and stars watermelon.” This year, Hixon got a packet of a birdhouse gourd seed, “which I’ve been dying to get my hands on. I’m pumped about growing them, drying them out, and maybe making some of my own birdhouses.”

Hixon wants to organize another swap in the fall, once gardeners have had a chance to let some of their own plants go to seed. “It’s really cool to just be part of that generational hand-down,” she said, both of food and of knowledge. “It is a small swap, but it’s just the beginning.”