The making of a biotech pioneer

How a Vermont farm boy turned fungus into just about everything

By Becca Tucker

When Eben Bayer left his parents’ Vermont farm to study mechanical engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, he figured he’d moved on from his rural childhood into a shiny future of tech.

Little did he know that he was on a detour that would end up coming full circle, to the realization: biology was technology. “Pigs and chickens were really cool technology too,” he said. “And it was much better technology” than turbines, engines and circuits. “It was compostable, circular, evolved over millions of years.” Fungus, too, which he’d seen lots of growing up in damp Vermont, growing on trees and on piles of woodchips.

“What if you were to engineer a woodchip composition that was mostly about the mycelium and less about the woodchip?,” Bayer wondered. “Biotech the way we think about it today was not a thing,” said Bayer. Twelve years ago, “the idea that you could grow materials was crazy.”

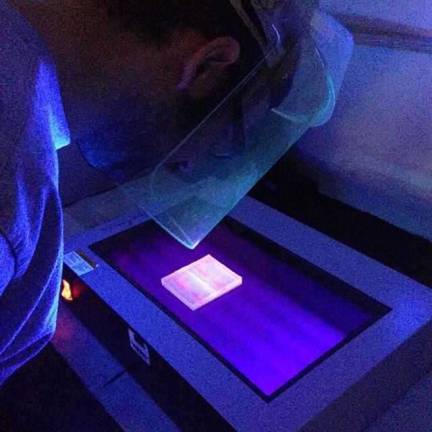

But there he was, growing discs made of woodchips and sawdust in his dorm room. His experiments turned out “poorly at first,” he said, “but then, pretty good.” He brought a coaster-sized sample to his professor, Burt Swersey, a legendary inventor and lecturer who developed and taught a course called Inventor’s Studio at Renssselaer.

If not for Swersey, the idea would probably have remained a cool college experiment. When Swersey saw what Bayer had grown, totally sustainable and compostable, “He was totally like, it’s not crazy, you should do it,” recalled Bayer. “We need better products for the planet.”

Not only should, but must.

Swersey, who passed away in 2015, was not one to let an opportunity pass. “Our students must be future leaders who will change the world and save people and planet,” he said in a taped lecture. “We must insist that they do, that they really do it. And don’t let them do nonsense.”

In the same lecture, Swersey recounted the moment of seeing Bayer’s early experiment. “‘Wow, this is not nonsense,’” Swersey recalled saying. “You have to do it.”

After Bayer graduated, he got a job for a company he’d spent summers with, making things like de-bombing robots for the military. Swersey kept calling him, asking about his mushroom experiments. Bayer assured his mentor he was going to work on his own stuff on weekends and in his free time. If you don’t do it full-time, you’ll never do it, Swersey told Bayer on the phone early one June morning a dozen years ago.

Bayer drove 20 minutes to work on the day he was supposed to start working nine to five. His new employer greeted him enthusiastically. Bayer announced he quit, drove home to his parents’ farm, and put up tarps in a canning room: his first lab.

Swersey became the first investor in Ecovative, a company that now employs more than 30 people with 10 interns coming soon. The young vibe of the open, dog-friendly office-workshop feels more like Silicon Valley than Green Valley, NY.

Ecovative’s first product was a completely sustainable alternative to Styrofoam that’s now used for shipping by the likes of Dell. The secret ingredient is, of course, mycelium, or mushroom filaments – grown from one of about 400 mushroom specimens that Bayer foraged himself from the woods. This particular fungus, which has become their go-to, is a ganoderma, similar to reishi. They chose it for its fast growth, strength, and ability to digest a bunch of different substrates, “on the theory that you’d want to localize it to many different regions.”

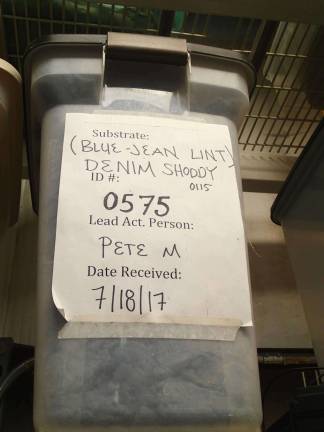

Here in the 32,000 square-foot space in a corporate park in upstate NY, the mycelium is inoculated into ground-up corn hulls or hemp hurds. Much of it is grown by farmers about 30 miles north, who must be pleased to be making money on what was until recently a waste product. The inoculated substrate sits in 10-pound bags for a couple days, while it “grows muscles” that will allow it to fight off contaminants like mold, said Shane Boland, 22, my tour guide.

The droplets that form on the bags is evidence of the mushrooms condensing, or breathing, which they do just like humans: oxygen in, carbon dioxide out. Boland slaps a bag, and the condensation disappears for a moment, then reappears. “Science,” he says happily.

Why did that happen?

“No idea,” he shrugged. “It’s cool though.”

After the two-day bulking up period, the now white-ish mixture gets broken up once more, fed with flour, and placed into a mold where it will grow into the intended product. For a planter, it sits growing on the rack for three days; for a small table, five days. Then the product spends about a day in an industrial dryer at between 180 and 200 degrees, which completely kills the mycelium, so that it won’t sprout mushrooms if it gets wet.

Packaging was a good first product for Ecovative. It was relatively easy to make, they could ramp scale up at their own pace, and replacing Styrofoam was important for the environment. Plus, who was going to stuff a house full of mushroom insulation made by a start-up no one had heard of? But there’s a small profit margin in packaging, so the company quickly branched out.

They’ve spent the last 18 months streamlining the process of making packaging materials, so that it can be replicated on a local scale without a bunch of scientists and engineers. “You can set up in a warehouse with a couple of people and start small and actually service your local community,” said Bayer. It makes no sense, he said, to be using local materials to make a product that then gets shipped to California, which they do today.

Democratizing access, worldwide, to the “platform” they’ve created is exciting to Bayer. Actually, it’s the entire point. Bayer, 33, who lives off-grid with his wife and newborn son, is an optimist. “We are just starting to crack the code of biology, and biology really is an unbelievable technology. Applied responsibly, it will let 10 million people live sustainably on this planet without harming spaceship earth.”

Spaceship earth? It’s an idea coined by Buckminster Fuller, a futurist from the 60s who designed the geodesic dome. You should think of earth as a spaceship hurtling through space, was his point, and we’re its life support system. So humans should work to keep the spaceship in good order.

Just plugging away at Ecovative’s two locations was not going to put a dent in the universe. “We’re not enough people,” Bayer said. “I want to get as many people around the world, especially artists and designers and students, thinking and creating with these mediums. Because I want other smart, creative people to come up with the next thing.”

Having proven the theory that fungus could be used industrially, Ecovative set to work to see what else they could make with mycelium. These days the better question might be, what can’t they make?

The day I visited, an operator named Dan Binetti was putting finishing touches on a pile of chair backs. Strong as plywood, they were made by inoculating hemp mats with mycelium. Until he started here five years ago, Binetti, from Mechanicville NY, spent decades as a printer operator. This place is a better one to work, he said, searching for the right word: “energetic.” Looks like it, from the basketball hoop on the wall of the manufacturing room. There are a fair number of desks without bodies, though, maybe a result of the company’s first major layoff last year, when Bayer had to let 18 people go.

Giant mycelium blocks were growing underneath the basketball hoop in plastic crates so large they have to be moved by forklift. They don’t seem all that exciting until you realize that these are “definitely the largest thing ever to grow in history of mushrooms,” as Boland put it. Until now, you couldn’t grow really large forms out of mushroom because the mycelium on the inside would suffocate, but the addition of black tubes delivering air to the heart of the block made the difference. Now they can make furniture and building material composite on a larger scale, driving down price.

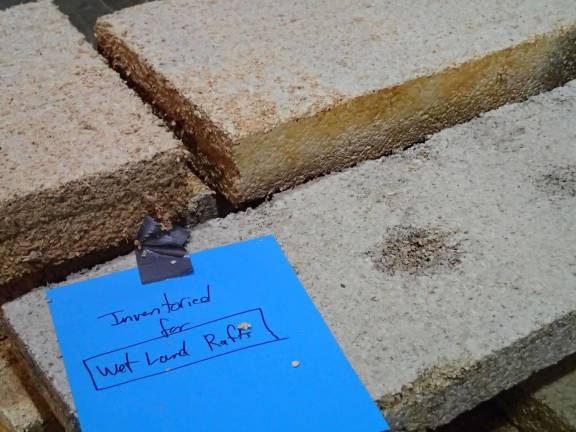

A guy with tattoos and earrings and a dust mask stood at a table, slicing a finished block into panels. One pile of panels was labeled “wetland rafts.” Holes would be drilled in these panels, Boland explained, aquatic plants inserted, and the rafts would be floated in a wetland in need of restoration. (They’ve experimented with making buoys, too. Foam buoys are, unsurprisingly, pretty bad for the ocean.)

Foams of varying softness have emerged as a hefty slice of their income pie, which can be used for anything from water filters to makeup pads to seat cushioning to shoe soles. Unlike conventional foam, which is full of toxins like flame retardants, these are completely clean and readily biodegrade.

A spinoff business called GROW.bio, which also runs out of the Ecovative headquarters, lets students and designers order kits to grow their own experiments, like a desk lamp. Designer Danielle Trofe of Brooklyn has made the mushroom medium her signature, installing a “cloud” of different-sized mycelium lampshades that covers the ceiling of a suite in a new hotel on the Brooklyn waterfront.

The newest invention to roll out of here is mushroom leather – “really good leather, which is a fundamental material that’s been with humans for thousands of years,” said Bayer. A batch is incubating in a trio of giant boxhouses that look like walk-in fridges the day of my visit. A California company called Bolt Threads bought the materials and named it Mylo. Stella McCartney (a vegan designer who made Meghan Markle’s after-party wedding dress) has just designed the first product, a handbag, out of Mylo that’s on display at a Fashioned from Nature exhibit at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Bayer hands me a square of the stuff, which has been dyed black with tea. It looks, feels, even smells like leather.

“I’m really excited on our leather,” said Bayer. “I think that that addresses an important waste problem and ethical problem in the animal industry. I will say personally I’ve raised and killed animals my whole life. I think that there’s a place for that in society, but I’m not a fan of factory farming.”

If mushroom leather seems weird, the future could get a lot weirder. Ecovative has sequenced the DNA of its top mushrooms, and is working on breeding and genetically engineering them to improve their performance. “It’s starting to get to the next frontier of biology,” said Bayer. Instead of just making materials and having them be dead, like wood being cut into a two-by-four, can we use materials to provide functions when they’re alive, he asked, like a tree making oxygen?

That could mean making mycelium into water or air filters that sense and react to their environment, responding to toxins by actually producing the compounds or enzyme needed to break down the toxins. It could look like building materials that respond to injury and recover, or could mean literally growing shelters in places where they are needed. Ecovative scored a $9.1 million federal defense grant last year to develop these kinds of next generation building materials.

In the meantime, Bayer is enjoying watching fungus go mainstream. A groundswell of start-ups from San Francisco to Singapore is already using the medium to grow products like furniture and packaging, localizing production. Each product is a “net good” for the planet, he said, “because they don’t turn into pollutants at the end of their life cycle.”

Now, “if the social construct can recover and keep up” – if we can get along, in other words, Bayer thinks we’re going to be in good shape. “We’ll have the tools to do it.”