A floating provocation

The farm on a barge in the South Bronx

By Becca Tucker

The traffic on the BQE exit ramp feels like it might never move again, the cars as idle as a painted ship upon a painted ocean. There’s not much to do but look down over the slate gray Bronx River. There, floating just off the concrete promenade, is something to see.

You can’t make out from here the fruit trees and bushes and corn and mint and Persian basil, but what you can see is a barge covered in green, the roof of a little white structure and an orange umbrella. It looks like an oasis — so close, but between the traffic and finding someplace to park, so very far.

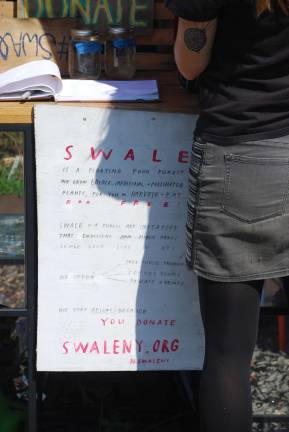

Finally I find a parking spot of dubious legality and hoof it a quarter mile into Concrete Plant Park, a reclaimed brownfield, to where the barge is docked. This is Swale, a floating food forest where anyone can walk on and forage, Friday through Sunday, 1pm-7pm.

Naseem Hammid, 18, welcomes me aboard and shows me a pair of Mason jars, one with murky river water, and a second full of clear water that’s made its way through the onboard filtering system comprised of carbon, coal and sand, and come out the other end clean enough to water the plants. Hammid is a member of the South Bronx-based Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, one of many groups partnering with Swale.

The Bronx, he explains, is ranked dead last of 62 counties in New York State on health indicators like high blood pressure and diabetes. “It’s crucial to have this relationship to plants and be able to pick them and taste them,” he said. “If people have it here, get to see it and be able to be close to it, they’ll fight for it in other places, supermarkets and all over.” Hammid is getting comfortable in the role of ambassador; he was featured in a short video by Al Jazeera in August.

The 100-foot barge, bought with $30,000 raised through Kickstarter, was once used for hauling sand. It’s just like the ones you see docked all over the Hudson, loaded with construction materials. But this one is piled high with soil and mulch, donated by the parks department, nurseries and Mast Brothers, a fancy chocolate shop in Brooklyn, which contributed cocoa husks. A woodchipped path snakes through the middle, where visitors can meander and pick from an ecosystem designed to be as self-sustaining as possible.

Swale is the brainchild of Mary Mattingly, a New York City-based artist who specializes in creating mobile eco-thought pieces. There’s not a huge amount that’s ripe the moment I visit, but a woman is munching purslane (an edible weed), and that morning a mother and her young daughter had gathered herbs to spice up their dinner. The eight apple trees are starting to get heavy with their fruit.

“Swale was an interesting kind of provocation,” said Lindsay Campbell, a research scientist with the U.S. Forest Service. “Of course New York City’s not going to feed itself from one floating barge, but she can capture the imagination of individuals that visit, of kids, telling them yes, you’re allowed to pick this food.”

Hammid emerges from the greenery holding an ear of corn. Now he has nothing to say. This is clearly the first ear of corn he’s ever picked. He shucks it. About half of it is bald, but the other half has nice yellow kernels. He takes a bite and nods.

Hammid would be breaking the law if he were standing a few feet to his right. New York City Parks Department rules say you can’t “mutilate, kill or remove” trees or plants from public land. But since Swale is on the river, it falls under the common laws of New York City’s waterways. Plus it can pop around the five boroughs and over to New Jersey, provoking conversations in its wake, and maybe some copycats.

The concept already seems to have leapfrogged onto land. Near the concrete silos that operated here until 1987, there’s an oversized bed in progress that’s being planted with what look like pollinator plants, grapes and echinacea. A sign announces that the Bronx River Foodway pilot program is coming soon, signaling what looks like a reversal of park policy.

Not everyone is convinced. “It’s a ridiculously dumb place to put this,” commented Bronx resident Andre Christopher Rivera, on Facebook. Charles Berenguer Jr., a photographer who takes pictures of wildlife around the Bronx River, worried it would be hard to protect the garden from vandals.

I ask Hammid whether he thinks this sort of thing could catch on elsewhere.“If people want it to happen, right?” He is sincerely asking, waiting for an answer. I nod, yes.

“Anything is possible,” he shrugs, and walks off with his corn.