Never-never farm

I pulled into my driveway, threw my seat back and passed out. That was what I’d promised myself — make it home and you can nap in the car, before closing the chickens in for the night.

But upon waking, I just flopped into the back seat. My windows were cracked, and I was a stone’s throw from the coop. If a raccoon grabbed a chicken, I’d hear it, I told myself, and rush to the rescue.

Could I help it if the last thing I wanted to touch tonight was the peach croustade I’d taken for the road? If the vision of farming that I wanted to slumber to was the idyllic one I’d come from, where children of all races willingly eat vegetables off the vine; where no plant appears to be under attack by any life-sucking pest although everything’s organically grown; where the foxgloves accenting rows of crops catch the setting sun?

I slept on until the cock crowed. Changing dress for T-shirt, I made the rounds: all was okay at my farmstead – I’d gotten lucky. But it was kind of dusty and second-rate. The sunrise made me wistful. It must be just glorious right now up at Katchkie Farm.

That’s the idea of the 60-acre educational farm: to get into your consciousness through your senses. Twenty-five minutes from Albany, Katchkie Farm lies “deep in the American arcadia, legendary for its gentle hills, rich farmland, and abundant streams,” as farm owner Liz Neumark puts it in her cookbook. When Neumark and her husband Chaim Wachsberger bought it in 2006, the bramble-covered land had never been farmed. Today it supplies a 600-member CSA and a big chunk of the certified organic produce used by Neumark’s company, Great Performances, one of the city’s biggest catering operations.

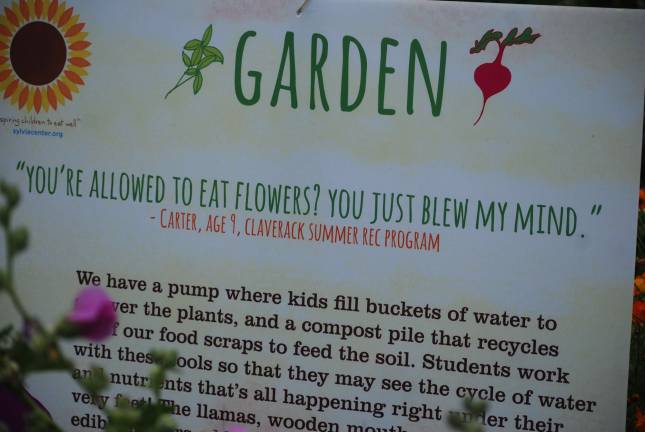

But this farm is not only, or even primarily, about cauliflower or kohlrabi. The night before, 330 people had gathered there for a farm-to-table dinner to benefit the Sylvia Center, the nonprofit that operates on its grounds, whose mission is “to inspire children to establish independent healthy eating habits.” It is the living legacy of Sylvia, the youngest of Neumark’s four children, who died suddenly at age six.

“We are in this incredible corner of bounty, in this beautiful country where our plates are full, we’re healthy, we make wonderful choices about what we want to eat,” said Neumark, to the diners gathered around long tables.

“Yet our own plates can’t be full unless we’re sharing with others, bringing knowledge of how joyful a kitchen can be to our neighbors.”

Of the 2,000 students who experience the Sylvia Center each year, 90 percent qualify for free or reduced lunch.

Before dinner, Dirt talked to two 13-year-old girls who were lingering under the apple trees, next to the llamas, a pair of pigs and the coop where chickens free-range. Merril Lewis and Nisaa Cora are in Perfect Ten, an after-school program for girls in the Hudson City School District. They reminisced about the dishes they’d cooked with ingredients from right here: frittatas, strawberry shortcake, lemon ginger muffins, empanadas, strawberry granola bars — but they got all gooey.

Merrill recently transferred from Hudson Junior High to Hawthorne Valley Waldorf School, which she liked better. “It’s like this,” she said, “a school on a farm.”

Up the dirt road, garden intern Emma Duffany, 21, pushed aside cucumber leaves to show two-year-old Grace Snyder a birds’ nest with a clutch of tiny beige spotted eggs. Grace then gamely waded into the vines, pulled on a cucumber, decided she couldn’t do it, and got some encouragement and a little help. Cucumber in hand, she started munching. “Get your own,” Grace told a man who looked like he was eyeing her produce.

Duffany searched high and wide for this internship, which combines farming with a social cause. It’s “more than just picking carrots eight hours a day,” she said. The nonprofit set-up relieves the pressure that can turn farming into drudgery. (An auction for hand painted benches opened at $1,000 each, and bidding was lively.)

Julie Cerny, farm education director and garden manager, led a tour of the children’s garden like the ones she gives to school groups, stopping every few paces to taste. It usually takes seven repetitions for kids to absorb information, she said. But when they cut open a watermelon and it’s yellow? Or they pull a carrot out of the ground and it’s purple? “Something happens there that they don’t forget,” said Cerny. “They don’t have to do it more than one time.”

Disclosure: In my sideline gig as a farmsteader, I deliver eggs to Neumark’s catering company, Great Performances.